Ukrainian President Zelensky urged the West not to wait until Russia strikes with nuclear weapons, but to launch a preemptive strike — without specifying whether it is nuclear or not. Many Western analysts, meanwhile, have no doubt that Russia is preparing to use tactical nuclear weapons somewhere on the territory of Ukraine. What does the Russian military doctrine say about this? And why, from a military-technical point of view, does it make no sense to use tactical nuclear weapons, but should we start with strategic ones? Naked Science understands the details.

First the quote. According to the Military Doctrine of Russia : "The Russian Federation reserves the right to use nuclear weapons in response to the use of nuclear and other types of weapons of mass destruction against it and (or) its allies, as well as in the case of aggression against the Russian Federation with the use of conventional weapons, when the very existence of the state is threatened." The decision on the use of nuclear weapons is made by the President of the Russian Federation."

However, in the West, some experts (and even the US president) believe that Russia [...] can [...] launch nuclear strikes in Ukraine because of the recent Kharkiv retreat. Where did the idea come from that Moscow plans to use tactical nuclear weapons in Ukraine? Does this make military sense? Let's try to figure it out.

To find out what Russia thinks about the use of nuclear weapons, a Western politician relies on a pop version of what is commonly said in the West (for example, here or here ). Additionally, such views have strengthened because in the Fundamentals of Nuclear Deterrence released in Russia in 2020 [...] [...], there is such a statement:

"The state policy in the field of nuclear deterrence ... guarantees ... in the event of a military conflict, the prevention of escalation of hostilities and their termination on conditions acceptable to the Russian Federation and (or) its allies."

The spent part (not the warhead) of the Iskander rocket, October 5, 2022, Ukraine. Contrary to the spring expectations about the fact that the Moscow rocket will soon run out, they quite continue to fly in the fall. SVO has become the largest precedent for the use of guided missiles in the history of mankind: during its course, they were used up more than in the entire previous military history combined Image source: Author unknown

What conditions are acceptable for Russia in the conflict in Ukraine? Apparently, among them is the complete cleansing of Russian territories from the Armed Forces. Since now four former Ukrainian regions have become Russian territories, some of the territories of which are still occupied by the APU, it seems that until the APU stops advancing, Russia can use nuclear weapons at any time, because it now considers these territories its own.

At the same time, in the Western and Ukrainian media (as well as military statements), Russia's losses in its own — of all kinds — are overestimated from several times to a dozen times. In addition, they expect that Moscow is about to run out of both missiles and all types of weapons in general. Despite the fact that the Russian military-industrial complex has not received Western components since 2016 due to sanctions (but at the same time it is growing, according to Western estimates), Western politicians believe that Russian weapons are made from Western components. And that's why they say en masse that the sanctions are already com/news/russia-cant-make-more-tanks-because-of-this-key-sanction-biden-official-says-204705566.html " target="_blank" rel="nofollow">deprived Moscow of the ability to produce even tanks (not that missiles).

T-90M, Uralvagonzavod, our days Image source: Rostec

But if you cannot produce weapons during a major military conflict, your defeat is inevitable. Accordingly, it is logical for Moscow to use nuclear weapons before it runs out of conventional ones, and thereby avoid defeat.

However, the previous considerations are true only if Russia really has military factories. In reality, Russian tank factories work in three shifts, and the same applies to the military-industrial complex as a whole.

Can Russia use tactical nuclear weapons in practice?

The APU does not seem to have many chances to hold those parts of the new Russian regions that they currently control. But at the same time, the underestimation of Russia's military potential by NATO experts is quite obvious. From this, Washington may theoretically be tempted to behave with such a weak state in the same way as it behaved with Yugoslavia, namely, to throw "peacekeepers" of the same NATO against it. Wouldn't Russia use nuclear weapons then? After all, such a conflict by conventional means threatens to put its existence at risk — and then the Russian military doctrine should just "work"?

But the probability of such a development is low. NATO is not ready for a conventional war with Russia any more than it is not ready for a war with him. According to the Ukrainian events, it can be understood that Moscow has the best air defense in the world in its hands, far surpassing the capabilities of the "Patriots". Without air supremacy, it is possible to fight against an army with strong artillery only with exceptionally heavy losses: about 80 thousand killed in the AFU confirm this. NATO, of course, is not ready to lose 80 or even 8 thousand people in an offensive war against Russia in Ukraine.

There is another problem: according to Ukrainian data (the Russian ones are closed), the Russian army releases an average of 550 cruise and ballistic missiles per month, their range is from 500 (Iskander-M) to 5,500 (X-101) kilometers. This is a lot: the United States has never produced so much in any war in modern history. The range of the X-101 is much superior to the Tomahawks. In addition, Russian cruise missiles are worse at shooting down air defenses: they have either on-board electronic warfare or a flight profile significantly lower than the Tomahawks, which makes detection difficult. Moscow's (quasi) ballistic missiles fly differently, actively maneuvering on the trajectory, which makes them, for today, practically non-interceptable.

X-101 at launch. A rocket weighing 2.5 tons, where more than half is accounted for by fuel, differs from other cruise missiles by the presence of an on-board electronic warfare system that causes air defense missiles to explode on "phantom" targets / ©The author of the video is unknown Without leaving the Russian territory, Moscow can shell X-101 cities on both coasts of the United States. And the Patriots are bad at shooting down low-flying cruise missiles. This threat is a strong deterrent. It's one thing to let the European members of NATO suffer, it's another to put their own territory under attack.

And yet, let's assume for a moment that the United States decides to intervene in the war, regardless of any losses and risks — and in this scenario, since NATO has more soldiers than Russia, the threat of Moscow's military defeat is not excluded. Is it possible for it to use tactical nuclear weapons (TNW) in response, at least in such conditions?

Tactically questionable asset

The term "tactical nuclear weapons" itself is not quite accurately outlined today. For example, the nuclear analogue of the X-101, the X-102 missile carries a megaton warhead. Is it still TNW or not already? The long range > 5500 kilometers seems to indicate its clearly non-tactical nature. Its power (greater than that of the warheads of intercontinental ballistic missiles) says the same thing. But, at the same time, formally cruise missiles with a nuclear warhead can be attributed to TNW. Only one thing is unclear: how to distinguish the use of such pieces from the beginning of the use of strategic nuclear weapons?

No one knows a reliable answer to this question. We will focus on the side of the question that is closer to reality: what, in fact, can be achieved by using tactical nuclear weapons?

A standard Soviet (and, if we take into account the warehouses, Russian) 152-mm nuclear projectile looks exactly like this (we hope that the photo is a mock-up, because the projectile at the Army-2022 stand was not well guarded). Since this is a typical projectile, it can be used by any army gun of this caliber, and at a great distance. At the same time, its power is only 2.5 kilotons, which is very little Image source: Philip Kobelev

Careful analysis shows that in fact very little. Take the current fighting in Ukraine. Russian troops directly at the front have an average density of less than 100 people per kilometer. In fact, it is even lower, and significantly: most of the troops are not actually on the front line, but are standing kilometers and tens of kilometers away from it. These are the rear areas of all levels, whose share in the modern army is above 50 percent of the personnel, and reserves, and much more. The APU has a higher density — up to 300 people per kilometer, that is, there are even more than 100 people per kilometer on the front line.

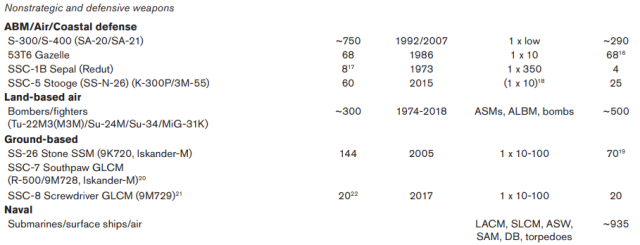

The idea of Russia's tactical nuclear arsenal (by which they usually mean all non-strategic nuclear weapons), as can be easily seen from the table, deviates very seriously from reality. Especially striking is the assumption that the number of missiles for Iskanders is equal to the number of launchers Image Source: AP

But this is too little for the meaningful use of tactical nuclear weapons. It is only for the defenseless and uninjured Hiroshima that the atomic bomb has shown great effectiveness. Troops on the battlefield are often in a growth trench, or in an infantry fighting vehicle, or in a tank.

The nuclear warhead of the Iskander is 50 kilotons. Let's use the publicly available calculator of the physical effects of a nuclear strike: what will such an explosion do on the battlefield? According to the experience of Totsky and other exercises, it will have to be carried out at least 350 meters, otherwise the radius of impact decreases sharply. But at such a height, a fireball from a 50 kiloton ammunition explosion will not even reach the ground, because its radius is 290 meters. The radius of severe damage (excess pressure of 1.38 atmospheres) [...] will be less than 900 meters, that is ~ 1.8 kilometers along the front. Gamma radiation, capable of killing most people, will cover 3.6 kilometers of the front.

The tactical result will be ambiguous. On the one hand, it seems that 3.6 kilometers one such blow will clear. On the other hand, it is obviously less than 600-700 killed soldiers of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, ~ 1 percent of the number of them that have already died during the SVO. It turns out that if the APU were constantly covered exclusively with nuclear weapons during its military operation, it would take more than a hundred TNW strikes to inflict the same losses on them that they suffered from conventional weapons. Such a number of blows is very, very much and very expensive (not to mention "reputational losses"). Wouldn't it be easier to continue working with cheaper conventional weapons? Especially when you consider that it does not cause comparable international resonance.

However, even such a calculation radically exaggerates the capabilities of tactical atomic weapons. The fact is that all these damage radii are for people standing in an open field. On the front line in the war zone, however, most people are in the growth trenches, and even in helmets. If they hear the sound of a cruise missile, they will lie down at the bottom of the trench.

Davy Crockett, a light infantry American tactical nuclear weapon. The USSR did not have a direct analogue of such a product, they believed that TNW should be used from longer-range protected self-propelled guns. The firing range from this installation, by weight close to the DSHK, is from 9.8 to 4.0 kilometers. The cost, however, was millions of dollars apiece Image source: Wikimedia Commons

But even if a nuclear warhead is brought by a high-speed Iskander, which is why no one will have time to lie down, a person who has only a head in a helmet above the parapet, in most cases will not die from an overpressure of 1.38 atmospheres: it is simply not enough for this. Those whose head was higher than the parapet can get a burn and a dose of radiation. But since only the head will "catch" gamma photons, most of the soldiers in the trenches will survive and live for decades after the atomic explosion. Just like a number of Hiroshima residents from the epicenter of the 1945 explosion, who were in the basement at the time.

Thus, the detonation of one tactical nuclear warhead over the line of trenches in Ukraine in practice will not kill even 300 Ukrainian soldiers. In order to achieve the losses that they have already suffered during the SVO, it would have been necessary to undermine more than 250 TNWs.

Armored vehicles are even less vulnerable to TNW. In 1953, the British tested their Centurion tank, detonating a 10-kiloton charge 320 meters away from it. Five mannequins with radiation sensors were put into the car, the engine was started and left running.

The same "Centurion" has not only survived to this day, but still looks great (of course, it has been repaired and painted more than once). It is important to understand that this tank was designed in the Second World War, so structurally it was not ready for the conditions of an atomic explosion Image source: Wikimedia Commons

The tank did not roll over. The engine [...] didn't stop until it had used up all the gasoline. And this is even despite the fact that the designs of the hinges and hatch valves were not strong, and all the hatches were torn off by this. Why the mannequins and the inside of the tank were "blown away" by a stream of grains of sand picked up by atomic flame and blown through open hatches. Three days later, a real crew was put into the tank — without the slightest decontamination, of course — and he left the landfill on his own (despite the terrible dustiness of the engine and transmission compartment, the engine did not break down immediately). Another 16 years later, the same tank went to the Vietnam War and even survived it.

Modern armored vehicles have normal, "anti-atomic" hatches that will not be torn off by an explosive wave. And it is also equipped with sights made of special glass that does not darken after an atomic explosion. The armored crew will not die from radiation, even if the TNW breaks out 400 meters from the tank in an open area. So the tank after this will not just keep the crew and mobility, but will also be able to continue the fight: to fire and hit. According to the US military, a modern tank can maintain combat capability even when a kiloton TNW is detonated 100 meters away from it.

Is it possible to use not Iskander as a TNW, but X-102 — after all, the charge there is much more powerful, a megaton?

Theoretically yes, practically no. And it's not even that something with a range of 5,500 kilometers is stupid to use on the battlefield. The problem is different: the X-102 flies several times slower than the Iskander, and anyone can hear it in advance. The Eastern Front teaches quickly: hearing the sound of a turbojet engine, soldiers lie down at the bottom of the trench. And this means that gamma photons will not get to them. And the trenches will be devastated by a blow within a radius of less than a couple of kilometers . That is, there will not be thousands of enemy soldiers killed even for a megaton charge of TNW.

It is important to note: such losses will follow only if the enemy did not prepare for the use of nuclear weapons at all and did not duck during the explosion. If, during the explosion, you are below the parapet line, then the situation changes. As the 1951 tests (Desert Rock exercises) showed, the sheep in the trench, without any helmets and bulletproof vests, did not receive any wounds, concussions, or dangerous radiation levels [...] even 800 meters from a nuclear explosion. Yes, then, in 1951, the nuclear explosion was not megaton. But for one and a half kilometers, the same situation will be observed at megaton power.

Normal officers, expecting an atomic strike on their positions, force the personnel to cut into the front wall of the trench a passage as wide as a person and a meter high, which is then torn off in a zigzag fashion 3-4 meters forward (if the ground is weak, the walls of the passage are reinforced with boards). In the case of hiding in them, the radius of continuous lethal destruction by any existing nuclear weapons will fall below a kilometer.

But the Soviet T-55 has already been fully adapted to the conditions of the atomic war: it will not work to disrupt its hatches with a close explosion, and the optics do not get dark Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Maybe. with tactical nuclear weapons, then does it make sense to strike at the columns on the march? But from the very first months of the war, the AFU completely lost the habit of moving troops in groups larger than a company. Russian aviation in Ukraine is actively working, and if a battalion gets hit by unguided missiles from a cabriolet, hundreds of people may die at once. And if a company — only dozens.

That is, the use of TNW on columns from a military point of view is not much more effective than on the battlefield. And, importantly, the enemy's losses will not be much higher than when using Iskanders with a cluster warhead. Which is also much cheaper than nuclear.

The defeat of reserves on the march with tactical nuclear weapons was considered at one time by the Americans in Vietnam, half a century ago. And they were the first to come to the obvious thought: the Viet Cong already avoids moving in large groups so that they are not destroyed by conventional bombs. In such conditions, the use of nuclear bombs does not make sense: hitting one of the countless mouths with atomic weapons is the same as firing a cannon at sparrows.

If tactical nuclear weapons are so weak, why is there so much talk about them?

If an atomic explosion on the battlefield kills only hundreds of soldiers and its military effectiveness is no higher than that of conventional weapons, then why have they been talking about it so actively lately?

Because people remember the experience of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — cities that are completely unprepared for a nuclear strike due to ignorance about its nature, when about 150 thousand people died directly in the days of explosions from just two bombs.

Almost no one thinks about the fact that on the modern battlefield there are only a few hundred people per kilometer, and not tens of thousands, as in Japanese cities. That they are mostly in the trenches, that is, analogous to the basements in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where people survived (after which they lived healthy for decades) even in the epicenter of the 1945 explosions.

Robert Kennedy and others are watching the tests of the Davy Crockett tactical nuclear weapon, an atomic explosion occurs 2.8 kilometers from the gun that launched the munition and its calculation / © Youtube That is why the initial enthusiasm of the military about tactical nuclear weapons was quickly replaced by disappointment in it and the decommissioning of all "Davy Crockets" and many other nuclear battlefield systems. During the Vietnam War, the US military thought about using such weapons somehow - if not at the enemy's military units, then at least to destroy his communications. There was, in particular, the idea to bomb the jungle trails along which the guerrillas were supplied with weapons and ammunition from North Vietnam.

But it turned out that it was not suitable for this either. The commission, with the participation of the famous physicist Freeman Dyson, carried out careful calculations that [...] showed that nuclear bombing of supply routes does not make sense, since they will not create an area truly impassable for the foot carriers who supplied the Viet Cong.

There will be no tactical explosions, but there is already a sediment from them

From all this it is quite obvious: there is no military sense in using tactical nuclear weapons at all. Atomic ammunition remains a miracle weapon only when hitting defenseless cities. On the battlefield, people are too dispersed and protected for atomic strikes to have serious military and economic advantages over conventional weapons.

If someone suddenly decides to start a nuclear war, he will most likely immediately put into action a strategic nuclear arsenal. With its help, in particular, tactical nuclear weapons storage facilities will be attacked, but mainly it will be used on military bases and cities. It is stupid to start with TNW, not only because it will not radically change anything on the battlefield (with limited use, which is written about in the West, not with hundreds of strikes), but also because the most logical reaction to TNW from the opposing block is to launch its ICBMs and "vitrification" of the cities of the country that TNW will apply.

Recall: in the West com/world/2022/oct/02/us-russia-putin-ukraine-war-david-petraeus" target="_blank" rel="nofollow">believe that it is not Kiev, but NATO, that will respond to atomic explosions in Ukraine to Moscow. The Secretary General of the latter directly made it clear that in this case a nuclear war would take place. Since Ukraine does not have nuclear weapons, we will talk about the Russia—NATO conflict.

Even if Moscow interpreted the "Fundamentals of Nuclear Deterrence" the way organizations close to the US government or the press do, there would be no reason to fear tactical nuclear strikes in Ukraine. Rather, it would be worth being afraid of using strategic weapons at once. In such a situation, tactical nuclear strikes simply do not make sense. After all, they will give NATO time to withdraw its troops from military bases (so that they are not covered by missiles right there), get their strategic forces ready, put all the submarines into the sea, and so on.

In this situation, the Russian army could have launched tactical strikes only if its leaders had completely lost their minds. With all the shortcomings of the Russian General Staff, there is no point in seriously discussing such a version.

So when the Western press [...] writes : "The United States criticized the Russian nuclear strategy of "escalation for the sake of de—escalation", which provides for the use of tactical nuclear weapons to prevent the expansion of the war to NATO countries," they do not understand what they are writing about.

speaking about how the United States (hypothetically) will respond to the use of TNW by Russia, he pointed out that NATO can destroy all the conventional armed forces of Russia in Ukraine, as well as the ships of the Black Sea Fleet. However, somehow without nuclear weapons. The stunning naivety of the general (NATO does not have the necessary arsenal of conventional weapons) is harmless at the moment. But if they mature to the idea of a preemptive strike in response to a non-existent threat, everything can change significantly.">

speaking about how the United States (hypothetically) will respond to the use of TNW by Russia, he pointed out that NATO can destroy all the conventional armed forces of Russia in Ukraine, as well as the ships of the Black Sea Fleet. However, somehow without nuclear weapons. The stunning naivety of the general (NATO does not have the necessary arsenal of conventional weapons) is harmless at the moment. But if they mature to the idea of a preemptive strike in response to a non-existent threat, everything can change significantly."> General Petraeus, the former head of the CIA, speaking about how the United States (hypothetically) will respond to the use of TNW by Russia, pointed out that NATO can destroy all the conventional armed forces of Russia in Ukraine, as well as the ships of the Black Sea Fleet. However, somehow without nuclear weapons. The stunning naivety of the general (NATO does not have the necessary arsenal of conventional weapons) is harmless at the moment. But if they mature to the idea of a preemptive strike in response to a non-existent threat, everything can change significantly. Image Source: This Week

In the Russian "Fundamentals of Nuclear Deterrence" there is not a word about "the use of tactical nuclear weapons to prevent the expansion of war." It says simply about nuclear deterrence in such a situation. That is, Moscow has no need to limit itself to tactical nuclear charges. The very idea of "tactical" nuclear strikes by the Kremlin is just a myth that has developed as a result of poor familiarization with the primary sources on the issue: Russian fundamental documents in the field of deterrence.

Nevertheless, the complete ignorance of the Western media and politicians about the issues raised above — and therefore their active discussion of the "strikes of the Russian TNW in Ukraine" — has its advantages. Let such fears be unrelated to reality, but they give rise to doubts in NATO about the usefulness of an open confrontation with Russia. In the end, even the refusal of the Secretary General of the alliance to rapidly accept Ukraine into it may well be part of such doubts.

The longer they last, the lower the probability of a full-fledged nuclear conflict between Russia and NATO. Which, in truth, hardly makes sense for either of these parties.