A huge number of myths have accumulated around the term "stealth", which have a very weak connection with reality. Naked Science understands what invisible planes are and whether they are really invisible to radars.

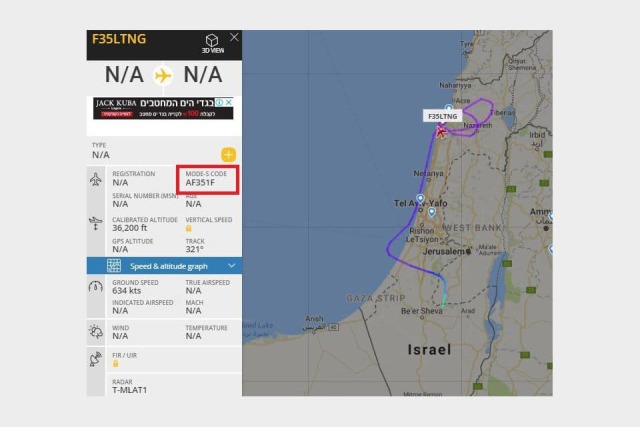

In July 2018, the location of the F-35I Adir (Lockheed Martin F-35 Molniya II) fighter-bomber, which performed combat patrolling of the sky over Israel, was displayed for several tens of minutes in the flight tracking service. This incident made a lot of noise at the time: an inconspicuous fifth—generation military aircraft turned out to be visible in an absolutely "civilian" application - is this really the vaunted "stealth"? However, aviation fans know that the appearance of "invisible planes" on services like Flightradar it is not something out of the ordinary.

During peacetime flights, the military often includes the same ADS-B transponders as civilian aircraft. This greatly simplifies navigation and increases safety in areas with heavy air traffic. Nevertheless, nothing prevents military aircraft from transmitting distorted or even fake data on open frequencies. This, of course, is condemned, since in some cases it can lead to catastrophic incidents. But data distortion is not at all inconspicuous.

A common opinion says that the Israeli Air Force in such an original way clearly showed all its neighbors its new arsenal. They say that the pilot was simply told not to turn off the transponder so that any dispatcher could see the newest F-35 in the sky. Although it is not necessary to exclude the factor of ordinary bungling. In the image - the Israeli F-35I is visible in the Flightradar24 service

Image source: Twitter@ItayBlumental

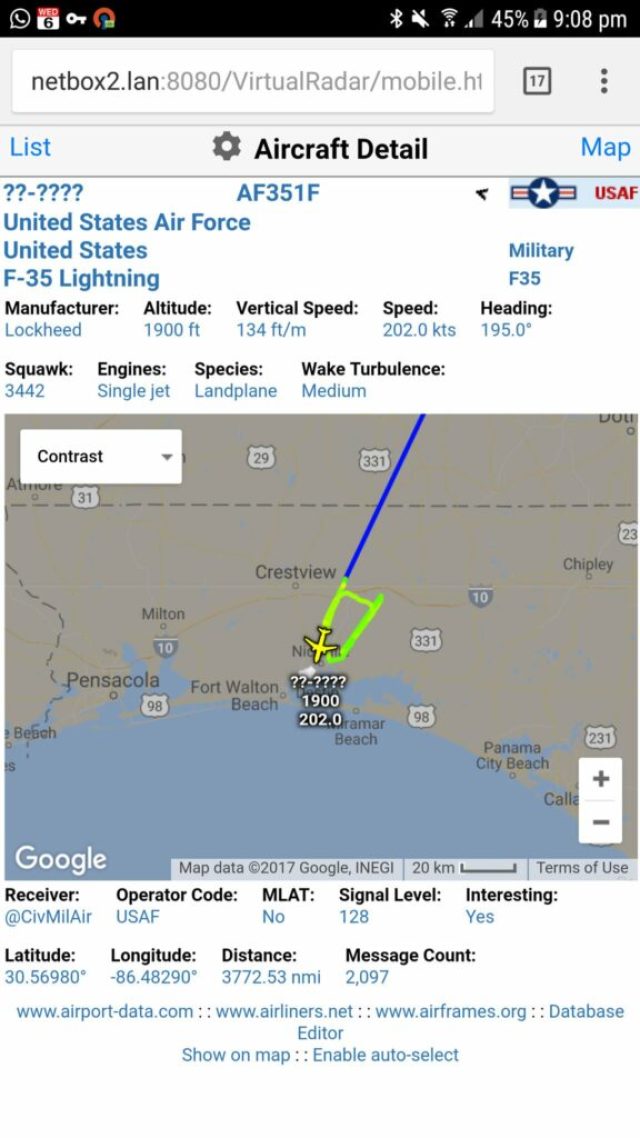

The F-35 flies near Eglin Air Base in the USA. Screenshot of a private air tracker

Image source: Twitter@CivMilAir

Civilian radars can't see stealth with the transponder turned off, but there are military radars — what's wrong with them? What is the difference for them between an ordinary plane and an invisible one, or do they also not notice it? In short, you can answer that they see, but not always — that is, rather badly and only up close.

In other words, the invisibility of the aircraft is achievable only in theory, and even then only in a very limited range of radiation. The modern complex of technologies, united by the unofficial term "stealth", is aimed at radically reducing the visibility of technology. The main idea is to make sure that the enemy notices us after we have come within striking distance.

This is achieved through a variety of complex technical solutions, tricks and application tactics. To explain how this happens, you will have to dive a little into the basics of radar and aerial navigation.

A needle in a haystack

Regardless of what methods we use - visual in the visible light range, in the infrared range or using radar - the tasks of dispatchers, pilots or air defense operators are divided into two classes: search and identification. To find an object anywhere (in our case, we are talking about air, of course), you can use the radiation emitted by it or reflected from it. In the latter case, radiation emanating from a third-party source and radiation that was specifically directed at the desired aircraft are also separated.

Air defense searchlights search for attacking aircraft during exercises in the sky over Gibraltar, November 20, 1942

Image source: War Office official photographer, Dallinson G W (Lieut), Imperial War Museum

This is most easily demonstrated by household examples. When we see an airplane in the sky, the eye receives reflected light from the sun (or another source — for example, the Moon or a searchlight). At night, there is no help from the luminary, so in order to avoid collisions, there must be flashing lights on the wings and tail of any aircraft. At a time when there were no radars yet, they were replaced by air defense searchlights — their light reflected from the fuselages of enemy aircraft was clearly seen by anti-aircraft gunners.

Aircraft with piston engines, with some luck, were detected with the help of acoustic direction finders. In fact, these were locators with large trumpets, in which ordinary human ears or simple electronic and mechanical devices played the role of a receiver. With the advent of jet aircraft, their effectiveness came to naught: the warning began to come too late.

After the invention of radars, nothing has changed fundamentally — only the detection distances have become larger. But the planes began to fly faster. In addition, it turned out that different wavelength ranges may have very different fields of application. For example, short-wave radars give high resolution and help very accurately determine the trajectory, as well as the flight speed of even an artillery shell. But their radius of operation is very small — the atmosphere effectively absorbs such radiation. In turn, long-wave radars allow you to see hundreds of kilometers around, but the "picture" turns out to be very inaccurate.

Is it a bird? Is it a plane?

With the identification of aircraft, everything is much more complicated. For a long time after the Second World War, all air defense calculations learned by heart the silhouettes of the aircraft of the probable enemy. With visual detection, this made it possible to quickly and fairly accurately determine what was flying overboard. Although no one was immune from mistakes anyway. With radio waves, there is no familiar image — at best, approximate dimensions, speed and direction of movement.

For civilian radars, the situation is saved by the transponder of the aircraft. The respondent constantly transmits a number of parameters of the aircraft: the identifier, speed and altitude, and in later systems, the exact coordinates. But when he is not there, everything becomes very difficult.

At first, radar operators, and then special computing complexes, according to a number of basic characteristics of the detected target, quickly identified it into the main classes. For example, if an object is flying at supersonic speed, does not maneuver and smoothly descends— it is most likely a rocket. If it moves at a constant altitude, changes course and maintains subsonic speed, it is almost certainly an airplane. However, something more unambiguous was needed to accurately identify the object.

The Tu-95 is made according to a normal aerodynamic scheme with a high-positioned wing. The tail is raised above the plane of the wing and has a different sweep from it, as well as a massive keel. All these elements perfectly reflect most of the spectrum of radio waves. To top it all off, the aircraft has eight propellers at once with four duralumin blades on each — which also greatly increases visibility. In the photo is a Tu-95 of the USSR Air Force, taken during an interception by an American naval aviation aircraft in 1974

Image Source: US Department of Defense

Avro Vulcan is a flying wing. Yes, it also has a massive keel, but without any additional horizontal surfaces, the leading edges of which perfectly reflect the signal. Other features inherent in specially designed stealth aircraft, this bomber did not have. But just one layout solution has already greatly affected its visibility for radars. Pictured is an Avro/Hawker Siddeley Vulcan taking off from Farnborough Airfield during an airshow in 2008

Image Source: CF38

Back in the middle of the XX century, physicists discovered that the amount of reflected radio waves weakly depends on the size of the aircraft. A striking example is the strategic bombers of the 1950s. The British Avro Vulcan and the Soviet Tu-95 took off for the first time at about the same time, and there was no question of any "stealth" at that time. But on the radar screens of those years, the domestic aircraft "glowed" like a Christmas tree, and its competitor from Foggy Albion was almost invisible. Despite the fact that Vulcan is only 40% smaller when looking at the wingspan and fuselage length.

A separate story is the materials used. From 1941 to 1953, the British Royal Air Force operated the De Havilland DH.98 Mosquito. This night fighter-bomber was almost entirely built of wood, plywood and textile fabric, which made it almost invisible to the radars of that time. However, it will not work to build an inconspicuous jet plane out of plywood and rags, the loads on the structure are too great.

De Havilland DH.98 Mosquito NF36 night fighter, tail number RL141. The photo was taken immediately after returning from a mission to the Royal Air Force Base Benson. In front of the plane are pilot Cogill and weapons operator Peter Verney

Image source: Peter Verney, mossie.org

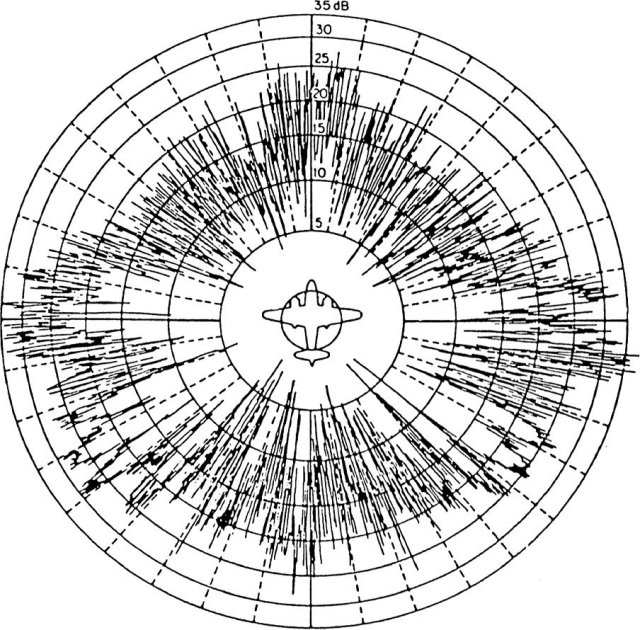

When the resolution of radar technology reached a certain level, it turned out that each type of aircraft has its own "picture" of the reflected radio signal, unique. So there was a "quest" for intelligence agencies around the world: to hunt for radar signatures, that is, diagrams of reflected radio beams characteristic of each aircraft model. By taking peculiar prints from the planes of a likely enemy by irradiating them with radars from different angles, it was possible to assemble a real "card file". Then such "casts" were loaded into radar computers, and it became much easier to distinguish fighters from bombers or missiles.

The mysterious term EPR

Almost always, in the context of low radar visibility, this abbreviation occurs. The effective scattering area (ESR) is one of the key characteristics of any modern military aircraft. Its physical meaning can be simplistically understood as follows: the EPR of a fighter equal to one square meter means that it reflects as many waves of a certain length as a meter-by-meter opaque surface installed at right angles to the emitter.

The EPR diagram is, in fact, the very "fingerprint" of the aircraft when "looking" at it in a certain radiation range. Knowing the distance to the target and reading its signature, it is possible to determine with high accuracy what kind of object is flying. The image shows an example of an EPR diagram of a Martin B-26 Marauder bomber at a radar frequency of 3 gigahertz

Image source: Skolnik, radartutorial.eu

As the above example with strategic bombers clearly showed, the size of the aircraft is not directly related to the EPR. The moment when engineers and scientists came to understand this fact can be considered the birthday of the concept of "stealth" in the modern sense. It took many years to create the necessary physical models and perform calculations. As a result, the military, as in a bad joke, received two pieces of news — good and bad.

The first was that the aircraft could be made virtually invisible to most existing radars. But the implementation of these theoretical developments turned into a very difficult and expensive task. In addition, at that time, more than half a century ago, there were not enough powerful computers and the necessary materials. Therefore, I had to experiment a lot.

Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II attack aircraft at the EPR study stand

Image Source: Griffis Institute, The U.S. National Archives

Trestle flyover for testing the effects of the electromagnetic pulse of a nuclear explosion on aircraft. During the Cold War, all US strategic bombers were irradiated with the help of special generators at the ATLAS-I test site. Contrary to popular belief, EPR studies have not been conducted on it. This structure is the world's largest man-made object made of wood, erected without metal fasteners (some metal was used to strengthen the caps of critically loaded wooden bolts)

Image Source: USAF

Study of the actual EPR and electromagnetic radiation from the onboard equipment of the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II fighter

Image source: The Howland Company, Randy Crites, Lockheed Martin

The embodiment of "in metal"

Contrary to popular opinion, the legendary SR-71 reconnaissance aircraft was not "stealth", but this does not mean that when it was created, they did not think about low radar visibility. Some of the surfaces of this unique machine were covered with special radio-absorbing materials. And under the skin, many structural elements were designed in such a way as to cause the re-reflection of radio waves and their mutual attenuation.

There is no exact data in open sources as to how much this helped to reduce the detection radius of the "Blackbird". Although the experience of the Soviet air defense forces showed that the SR-71 is a difficult target to track, it was not caused by its low visibility. It was possible to "guide" the scout using radar only manually, since it had powerful electronic warfare equipment on board. The automation of Soviet radars of the 1970s and 1980s did not allow us to effectively filter out interference.

Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird during experimental flights under the LASRE program for NASA purposes

Image Source: NASA Photo, Lori Losey

The first real "stealth" was no less legendary Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk ("Night Hawk"). When creating this strike aircraft, all the technologies known at that time to reduce visibility were used for the first time:

- It was made according to the "flying wing" scheme - without additional tail or front tail; despite the subsonic maximum speed, the leading edges of its wing had a very large sweep;

- All external elements of the fuselage were positioned at precisely calculated angles so as to reflect radio radiation away from its source; the keels were located at an acute angle to the fuselage;

- The blades of the engine compressors are one of the most noticeable parts in the radio range in the frontal projection, so the channels of the air intakes of the power plants were S-shaped; this reduced the efficiency of the engines, but shielded them;

- The fuselage and all external surfaces were covered with radio-absorbing materials, as well as the air intake channels inside;

- Any external elements - antennas, sensors and sensors - were either closed with special covers or made retractable;

- The hatches of the internal weapons compartment and all the covers of the technological openings had a sawtooth edge with faces parallel to the edge of the wing; this provided only a few angles from which the aircraft was "visible" a little more;

- To prevent missiles with an infrared homing head from effectively targeting it, the engine nozzles were brought to the upper plane of the fuselage; in addition, they had a rectangular cross-section to improve the mixing of hot exhaust with the environment; in addition, an additional volume of air was supplied behind the combustion chambers to reduce the temperature of the exhaust gases.

Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk Stealth Tactical Bomber

Image Source: Lockheed Martin

Millions of pages have already been written about the problems caused by such an aircraft design, so let's mention them briefly. The "flying wing" is an extremely unstable aerodynamically scheme, which is why it was necessary to use an advanced electric control system. Since the aircraft's own radar is a powerful unmasking element, the F-117 did not have a radar on board. Therefore, he could use weapons only with laser guidance or by external targeting.

Finally, additional means of self-defense — fired countermeasures ("traps") and electronic warfare stations - could not be combined with low visibility. Therefore, the only thing the pilot could count on when an attack alert was triggered was his skill in performing an evasion maneuver, and even the fact that due to the "stealth technology" the missile flying towards him would lose its target by itself.

Progress

With the development of computer technology, materials science and against the background of general progress in aviation, the concept of low visibility was able to be combined with almost any requirements for a military aircraft. After the generally quite successful "Nighthawk", absolutely fantastic cars appeared. Let it be insanely expensive, but the Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit has shown that a strategic bomber with a huge range can also be practically invisible to radars — and at the same time have full functionality corresponding to its purpose.

An inconspicuous Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit strategic bomber during the first flight shown to the general public, 1989

Image Source: USAF

And the appearance of the Lockheed /Boeing F-22 Raptor was a clear demonstration of the possibility of using "stealth technology" on fighters. Undoubtedly, more modern inconspicuous aircraft are created using even more advanced technical tricks. Special radar blockers appeared in the nozzles of the engines. These details also reduce the visibility of the aircraft from behind, covering the turbine blades, which cannot be covered with a radio-absorbing material.

In the XXI century, it is difficult to imagine the development of a new military aircraft without the use of stealth elements. Yes, contrary to popular belief, this technology does not provide complete "invisibility". But fighters are not ordered by ordinary people either — the military perfectly understands the price of every extra kilometer that the plane will fly, being undetected. In addition, any new technology allows you to come up with new tactics of application or improve existing ones.

The second participant of the Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) competition is Northrop/McDonnell Douglas YF—23. If this prototype had won, instead of the F-22, the US Air Force would have received the F-23

Image Source: U.S. Air Force, USAF Edwards AFB, National Museum of the USAF

In practice

"Stealth" is not a panacea and not an ace in the hole, but a great tool. No aircraft during the battle does not fly in proud solitude, it always acts in conjunction with many other types of equipment. For example, fighters during an attack have long been invented to cover with electronic warfare aircraft. And give them target designation from a much more powerful scout flying out of reach of the enemy's air defense. An inconspicuous fighter, working in such conditions, gets even more opportunities; and to cover it, at least, less resources are needed.

A separate plus of aircraft with a low effective scattering area is that they are easier to simulate. To confuse the enemy's defense, there are special drones or missiles that act as false targets. It takes much more energy to pretend to be a fourth-generation fighter with an EPR of one and a half to two square meters than to imitate some F-35 (fifth generation) with its supposed few centimeters. And this means that such a bait will be able to fake more targets and will work longer

And we didn't know he was invisible!

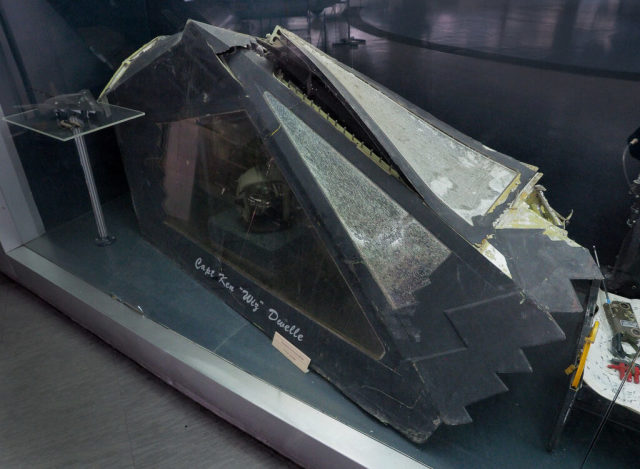

"But, wait a minute, we know the price of all these "stealth", - an inquisitive reader will say. And pointedly points his finger in the direction of the Balkan Peninsula. Indeed, the only F-117 ever lost in combat was shot down during the war of NATO forces against Yugoslavia on March 27, 1999. Along with many other notable cases that occurred during the fighting, this is the clearest example of how a properly planned, prepared and conducted operation can have a stunning effect even against an enemy significantly superior in technical equipment.

One of the variants of the S-125 Neva air defense system, which was in service with the Serbian army

Image source: Srđan Popović, Wikipedia

The hunt for the "Nighthawk" was critically important for the Yugoslav military from a propaganda point of view. And her organization was approached incredibly carefully. The air defense battery, commanded by Zoltan Dani, was trained to collapse and deploy the firing position of the S-125 Neva anti-aircraft missile system five times faster than the standard time. It is difficult to say at what cost such efficiency was achieved, but it allowed the air defense system to be relocated faster than the enemy could react.

Thus, the surprise of the attack was ensured. In addition, the Yugoslav side had spies near the Italian airbase where the American F-117s were based. They provided operational data on how many and which aircraft went on a combat mission. In turn, the US Air Force made several mistakes at once. Their causes are unknown, but the consequences were very severe. And it's not even about the loss of an ultra-expensive aircraft or a blow to reputation — after the incident, the entire tactics of using "invisibles" were revised in general, as well as a number of personnel changes were made. About what kind of force the commanders who led the operation received a scolding, we can only guess.

On that ill-fated night, Lieutenant Colonel Dale Zelko's F-117 took off and headed for the target in proud solitude. The "support group" represented by electronic warfare aircraft could not join him due to the sharply deteriorated weather. And Zelko's flight route was exactly the same as in the previous two days of night attacks — no one bothered that it would be nice to change it. As a result, Dani's subordinates knew that stealth was heading towards them along a known trajectory, and interference to radars would be minimal or absent at all. The Yugoslav military turned on the radar for a few seconds and immediately changed the location, acting in an environment of complete radio silence. So they could not be detected by American high-altitude scouts. The F-117 was detected at a distance of about 10-20 kilometers, and after a few seconds hit the missile almost at point-blank range.

The cockpit light of the F-117 shot down in Serbia. The exposition of the Belgrade Aviation Museum

Image source: Petar Milošević, Wikipedia

The operation was carried out so brilliantly that after the war, admiring Zoltan's skill, Dale (being already retired) came to meet him personally. Summing up this story, we can say that no small visibility will save you if you use it incorrectly.

And without any "stealth"!

A counterexample of the above story with the lost F-117 is the American exercise NORPAC FleetXOPS 82, conducted near the Kuril Islands and Kamchatka in 1982. For four consecutive days, a full-fledged carrier strike group (AUG) operated just 400 kilometers from the nearest Soviet airfields of long-range strategic aviation in the Far East. All American ships and aircraft were operating in full radio silence, with the exception of a couple of incidents. Carrier-based aircraft carried out multiple training attacks on coastal infrastructure facilities. The aircraft carrier Midway and its escort ships also performed many exercises.

And all this passed without the slightest detection, even by means of satellite reconnaissance. And even more so without any "stealth". The secret was in well-coordinated work and cunning tactics. The group constantly changed its position and tried not to fall into the limited "field of view" of Soviet satellites. All communications took place either by visual methods or using short-wave directional radio transmitters.

1991, the aircraft carrier USS Midway (CV-41) returns to Pearl Harbor from a base in the Japanese city of Yokosuka. On the empty flight deck, "goodbye" is laid out. Six months later, the ship built back in 1942 will be decommissioned and converted into a museum

Image source: Galen Walker, US Department of Defense

Target designation was carried out either in passive mode or by illumination from AWACS aircraft, which were launched from another aircraft carrier - Enterprise. And he, in turn, was several hundred miles to the south and was ready at any moment to also "dissolve" in the ocean.

The legend of the Soviet Genius

In the context of the history of the development of "stealth technology", there is often a mention of the Soviet scientist Ufimtsev Pyotr Yakovlevich. According to legend, his publication "The Method of edge waves in the physical theory of diffraction" was recognized by the party leadership as not of interest from the point of view of the national economy. Therefore, in 1962 it was published, among other things, abroad. American experts at that time had been struggling for many years over the problem of reducing the reflection of radio waves from various objects. But they couldn't decide. And this "unrecognized article in the USSR" actually saved them and helped to make the first "stealth". In support of this story, the fact is usually cited that since 1990 Ufimtsev moved to the United States and began working at Northrop Grumman on the B-2 Spirit.

There is some truth in all this, but in general the story is not so romantic. Both in the USA and in the Soviet Union, the issue of radar visibility of aircraft was actively studied. The work went on with varying success, and both sides faced great difficulties. But when Pyotr Yakovlevich's publication appeared, it served not as a reason for exclamations of "Eureka!" from the mouths of American engineers, but as a way to attract even more funding. Like, you'll see how far our main enemies have advanced. The absence of equally successful projects of inconspicuous aircraft in the USSR is not explained by the short-sightedness of the party leadership. Domestic aircraft designers had great difficulties with the development of the necessary materials, and funding was perhaps not as generous as their colleagues overseas.

Instead of a conclusion

"Stealth" is like a gun hanging on the wall. Both in Chekhov's plays and in Guy Ritchie's films, this is an important detail. But in one case, this is just one of the effective artistic techniques. And in the other - a spectacular plot engine, without which the narrative can turn in the other direction.

In ground technology, the armor has long lost to the projectile in direct competition. Now it only protects the combat vehicle from related threats, outdated weapons and allows you to get closer to the target at an attack distance. In aviation, about the same thing happens. Low visibility in all possible detection ranges does not protect the aircraft. But it often allows you to strike first.

It doesn't matter if the radar sees an approaching fighter. Most likely, he will see it. The main question is how big the distance at which it will be possible to notice it will be.