American science columnist Megan Bartels, in an article for Scientific American magazine, considered options for decommissioning the International Space Station. Naked Science translated her article for a Russian-speaking audience.

The International Space Station, which is larger than a football field and weighs almost 450 tons, should be returned to Earth after a while. This is a difficult and dangerous process.

For almost a quarter of a century, astronauts were constantly present on the ISS, scientific experiments were conducted, it was the main and beloved bastion of humanity in space. But despite the success of the project, the days of the ISS are numbered.

In the coming months, NASA will consider commercial proposals for devices capable of decommissioning the station, that is, safely lowering it into the Earth's atmosphere so that it burns down there. The agency stated that it is ready to pay almost a billion dollars for this service in order not to rely on Russian equipment. The dramatic finale is scheduled for the beginning of the next decade, but has already become a sensitive issue for aerospace engineering and international relations.

"The ISS is the most important symbol of international peaceful cooperation. In the field of peaceful cooperation, I think many would describe it as the largest project ever launched in the history of mankind," said Maya Cross, a political scientist at Northeastern University

Canada, Japan and European countries also participate in the ISS program, but it is mainly the brainchild of the United States and Russia, one of the few areas of sustainable partnership between these two countries over decades of difficult relations. The first modules — one from the USA, the other from Russia — were launched into orbit at the end of 1998. And the first crew — one astronaut and two cosmonauts — settled there in November 2000. Since then, the ISS has been permanently inhabited and has far exceeded the originally planned 15-year service life.

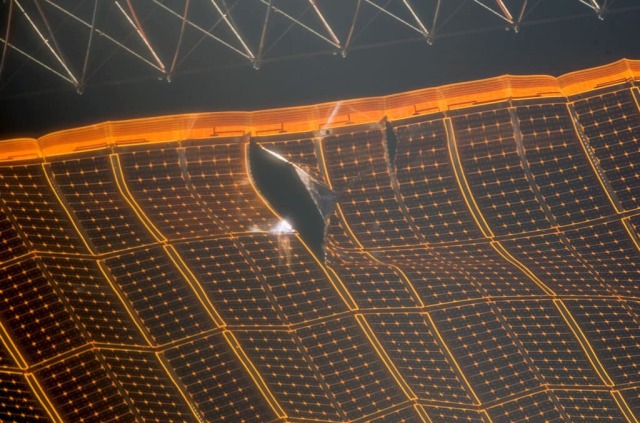

|

| An example of damage to the ISS at an early stage of its life, a decade and a half ago. |

| Source: Wikimedia Commons |

But nothing lasts forever under the moon. "I really do not want it to cease to exist, and it is a pity that it will be retired, but it is impractical to keep it in orbit indefinitely," said George Neeld, president of Commercial Space Technologies and a former member of the NASA Aerospace Safety Advisory Group, a committee that called on the US space agency as soon as possible rather, to develop a strategy in case of the end of operation of the ISS.

The further fate of the laboratory is connected with its location in low Earth orbit, in the rarefied upper layers of the Earth's atmosphere. There, everything that is gaining altitude decreases over time, as it is slowed down by the constant flow of atmospheric particles and is pulled back to our planet.

Without periodic overclocking, a spacecraft in low orbit would have lost speed, and therefore altitude, eventually plunging deep enough into the atmosphere to fall apart and burn up. The ISS orbit is maintained mainly due to the launches of Russian Progress cargo ships, which, after docking with the station, periodically turn on their engines to counteract the constant decrease of the ISS.

Theoretically, NASA and its partners can transfer the station to an orbit beyond the Earth's atmosphere. But it is extremely expensive to lift all this mass to such a great height. And even if the ISS were abandoned and buried in such a high orbit, it would still pose a danger: being very old and bulky, the station would eventually inevitably fall apart into a huge number of debris that could damage other satellites.

|

| To fix such malfunctions, astronauts (or astronauts, as in this case) have to be sent into space. The photo was taken on November 3, 2007. |

| Source: Wikimedia Commons |

"It is undesirable to leave it in orbit. You could treat it like a museum, but it will fall into disrepair and fall apart," added Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, which also tracks satellites.

According to Neeld, dismantling the ISS is impossible, since its disassembly was not envisaged, and any attempts to do so are fraught with serious risks due to aging components that have been in extreme space conditions for more than two decades.

If the space station stops moving in orbit, it will have to burn up in a blaze of glory. This can happen in two ways: by deliberate descent into the atmosphere, during which it will collapse, or by what engineers call an "uncontrolled descent from orbit", that is, the ISS will fall to the surface of the Earth along a random trajectory. The latter option is spectacular, but undoubtedly dangerous. The International Space Station is bigger than a football field, and more than 90 percent of the Earth's population lives in its orbit. So far, falling debris from spacecraft has not caused much damage to people and structures, but the ISS will be the largest object ever to leave orbit, and this can easily change the situation.

"An uncontrolled gathering can lead to significant destruction on the Ground, including injuries and deaths, and property damage. It wouldn't be a good day," Neeld warned.

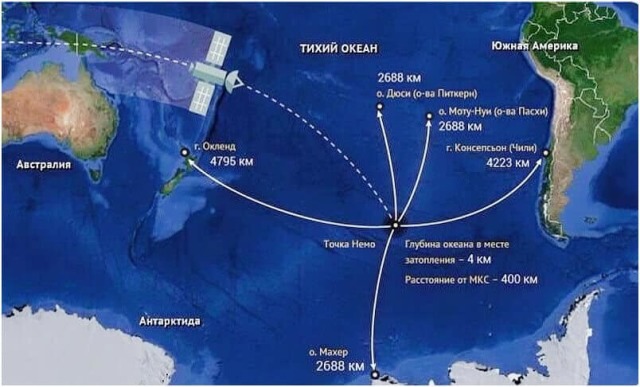

According to NASA representatives, the safest way to bring the ISS to Earth is to send it to sparsely populated areas of the South Pacific Ocean to reduce the risk of damage.

This is a difficult task, because the station makes one revolution in about an hour and a half, covering about 400 kilometers of the Earth's surface every minute. The terrestrial trajectory is constantly changing as the planet rotates. The longer the ISS stays in the atmosphere, the more debris it will spread along this trajectory, increasing the likelihood that some breakaway fragment will cause destruction on the surface. But the station's fall should not happen too quickly either: if the ISS is sent into the atmosphere with too much acceleration, increased air resistance can tear off large segments from it, such as solar panels or individual modules, which will then independently enter dense layers in an unpredictable and uncontrolled way.

The problem is compounded by the irregular geometry of the station, so it is extremely important to maintain its stable orientation when diving into the atmosphere. If the ISS starts tumbling during descent, the rocket that will take it out of orbit will also change its position, which will lead to a dangerous deviation of the ISS from its course.

Add to this the fact that the Earth's atmosphere is very unstable: it gets thicker and thinner during the 11-year cycle of the Sun's activity and changes during the transition from day to night and back.

"The de-orbiting of such a large object as the International Space Station depends very, very much on how things are with the density of the atmosphere. In principle, this parameter cannot be predicted in advance," said David Arnas, an aerospace engineer at Purdue University.

Taking into account all these factors, the process of taking the ISS out of orbit would ideally look like this. After several weeks or months of natural orbital descent at an altitude of approximately 400 kilometers above the Earth, a special ship docked to the space station will start its engines. After the ISS has traveled about half the way to the surface of the planet, it will begin to experience a destabilizing effect. At an altitude of about 200 kilometers, controllers will adjust the trajectory of the ISS, controlling the operation of the rocket engines so as to turn the station's close-to-circular orbit into an ellipse with the point closest to Earth, or perigee, 150 kilometers above the planet. This will help to minimize the time that the station will spend in lower, denser layers of the atmosphere during the final stage of descent.

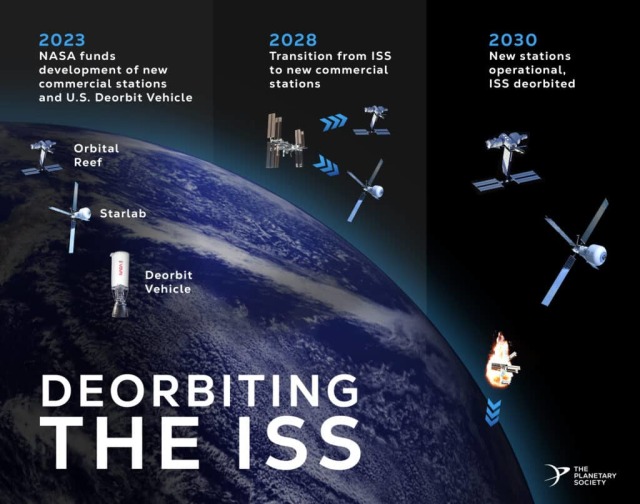

|

| One of the schemes for the ISS data from orbit. |

| Source: The Planetary Society |

From this 150-kilometer perigee, at the command of the Mission Control Center, the rocket will give the station the last impulse, pushing it even lower — so that it falls in the South Pacific Ocean.

"The whole world will be watching this," Cross recalled. Therefore, a lot will be at stake.

What is needed to implement this daring plan? Until recently, NASA representatives stated that several Russian Progress ships — perhaps three — would bring the ISS out of orbit together. But this plan was tentative at best because of the difficulties in coordinating the work of individual ships.

"Even under favorable conditions, it would not be easy. It is necessary to build, launch, dock several Progress ships in a very short period of time so that they complete their task," explained Neeld.

As for the US-Russian partnership on the ISS, things are not going well. Due to the conflict in Ukraine, relations between the two countries have reached their lowest level since the Cold War, which has complicated cooperation on the space station.

In addition, Russia admitted that it would withdraw from the partnership without waiting for NASA to be ready for this, and did not give any guarantees that in such a scenario it would provide Progress ships for the controlled descent of the ISS from orbit. Therefore, an American ship capable of returning the ISS to Earth is becoming a desirable target for NASA and the United States.

But if NASA wants to get a device designed on the basis of those ships that are now part of the global space fleet, McDowell added, then the choice is not so great. "The first thing that comes to mind when you start thinking about it is that ships like this just don't have enough power for the final short—term pulse," McDowell said.

The most suitable of the existing technologies, in his opinion, is the European service module of the Artemis program, which powered the unmanned Orion capsule on its journey around the Moon last fall, and at the end of this decade should help land people on the lunar surface. Everything else, according to McDowell, is either too weak, too powerful, or simply unable to carry enough fuel to complete the task, so NASA is requesting commercial proposals for a new, purpose-built vehicle.

Regardless of which device NASA chooses — a new one or an existing one adapted for this task, the decision will affect not only US-Russian relations, but also many others underlying cooperation on the ISS.

The completion of the operation of the space station assumes the same general responsibility as its construction and maintenance, but the published NASA documents do not clarify whether the Canadian, Japanese, European or Russian space agency has signed up to the plan implemented by the United States.

The approaching end of the megaproject provides food for another topic of international discussions on the future partnership in space. NASA is already building bilateral partnerships with countries interested in exploring the Moon under the Artemis Agreements, although Russia is not one of them. China, which has long been prohibited by US federal law from participating in the ISS, has now entered the forefront of the space industry with its own orbital laboratory, as well as robotic lunar and Martian missions. Whether the death of the ISS will lead to a defusing of tensions between the United States and China remains to be seen.

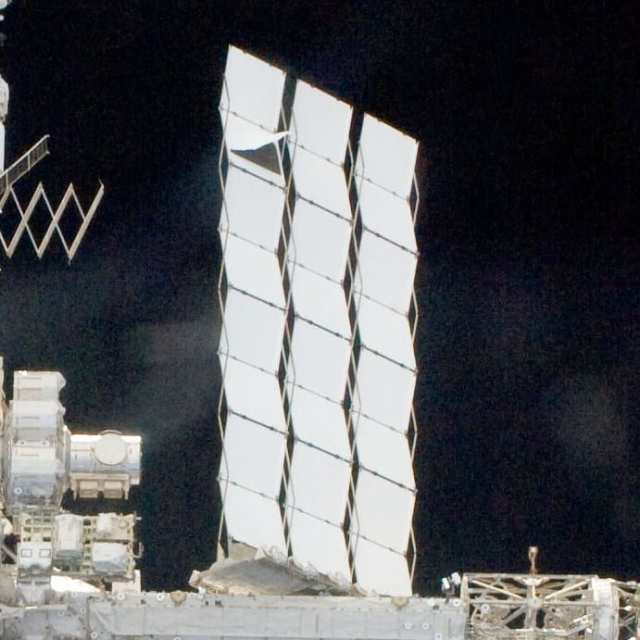

|

| Damage to the ISS cooling radiators. Without proper cooling, the survival of people at the station would be extremely difficult. |

| Source: Wikimedia Commons |

One thing is obvious, political scientist Cross stressed, no future international forms of partnership will be able to repeat the ISS, which is likely to remain a unique, outstanding achievement.

"The range of countries involved in space exploration will look very different than in the days when Russia and the United States began to cooperate on the ISS," she said, adding that she hopes to maintain partnerships until the dramatic end of the space station.

Whenever the ISS returns to Earth, its sinking will be one of the most infamous milestones in the long and glorious history of space flight. "It is not often possible to make such a maneuver. They will be very, very nervous when they have to do this," Arnas summed up.