Engineers have developed an underwater navigation beacon that does not require power supply. It is based on a transponder that responds to sonar signals, and at the same time is powered by the energy of its sound waves. The system calculates the distance to the transponder based on the delay time of the signal and its content, and to overcome the echo, signals in a variety of frequency ranges are integrated. The article is published in the proceedings of the conference HotNets ’20: The 19th ACM Workshop on Hot Topics in Networks.

The water is opaque to short and medium radio waves, and therefore GPS navigation does not work under water. Several years ago , the development of acoustic GPS for American submarines was reported, but it is unclear whether it will be available to civilians. In addition, it does not imply the possibility of creating an analog of a GPS tracker — a small light device that transmits data about its position to the operator. However, ichthyologists really need an analog of such a device for the aquatic environment, since it will allow tracking the movements of individual fish. In addition, a convenient navigation tool will be useful for underwater robots.

As an alternative solution, over the past few years, a group of engineers led by Reza Ghaffarivardavagh from the Massachusetts Institute of technology has been developing an echolocation beacon-a transponder that responds to the navigation station's sonar signals. The station listens to its responses, and based on their delay and the speed of sound in the water, calculates the distance to the object. The disadvantage of such a system is that the transponder requires a large battery for long operation, which, again, limits mobility.

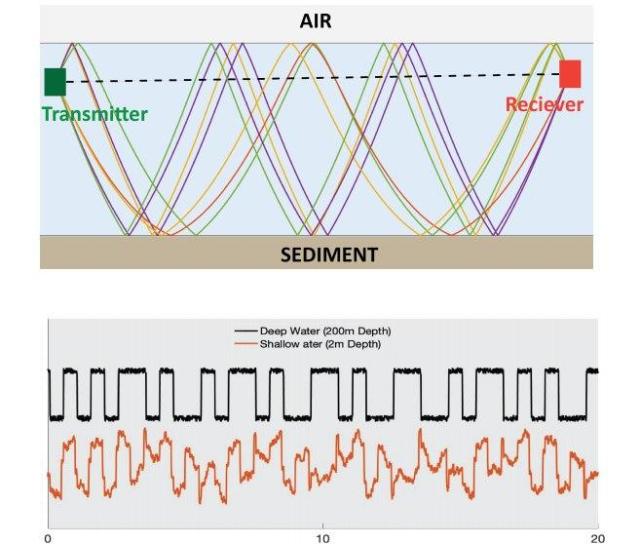

Last year, developers tested a transponder that doesn't require a battery, but instead uses a piezoelectric generator to convert sonar sound into electricity. However, the test sample was not suitable for navigation by itself, because before issuing a response, it needed to accumulate electricity for a time that varies depending on environmental conditions (within hundreds of milliseconds). In addition, the sound is repeatedly reflected from the bottom and from the surface of the water, creating an echo, so when the transponder finally responds, it will be impossible to understand whether it responded to a direct signal or to a reflected one.

Now the same research team has tested a non-volatile transponder and developed a prototype underwater navigation system based on it. The high accuracy of this system is ensured by the accumulation and analysis of a large amount of data. First, the tracking station emits a pulse at a certain frequency for a few seconds, which is modulated by a conditional code. Then, when the transponder accumulates power, its response will depend on where it started reading the code. After recognizing this location, the station will calculate the delay in collecting energy, and make an adjustment for it.

But the exact position of the transponder after this is still unknown, since the signal is hindered by an echo. Therefore, after receiving the first response, the station changes the frequency, and the cycle repeats. After accumulating data over a wide frequency range, the system calculates the true distance to the device based on a large data set. When the echo is too strong, for example, if the case occurs in shallow water, after receiving the first signal, the station sends a code with increased intervals between characters. This increases the time to update the position, but gives a gain in accuracy.

The system has successfully demonstrated its performance during tests in the river at a distance of several tens of meters. The operating frequency varied in the range from 7.5 to 15 kilohertz in 75 Hertz increments, each pulse lasting six seconds, which was enough to position slow-moving objects with an accuracy of ten centimeters. However, before these developments can be used to create a full-fledged underwater tracker comparable to GPS in accuracy, a number of problems must be solved, including learning how to calculate not only the distance to the transponder, but also its three-dimensional position in the water column. In addition, it is not known what problems engineers will face when trying to scale the system to work at multi-kilometer distances.

If successful, underwater transponders will greatly help ichthyologists, because on land and in the air, zoologists have long used GPS trackers. For example, they were able to find out how false vampires survive the dry period, as well as that Mediterranean gulls have adapted to humans and prefer to live in economic areas.

Vasily Zaitsev