According to estimates by an international team of researchers, the lunar craters contain platinum and other precious metals worth more than a trillion dollars. They were brought by asteroids that have been bombarding the surface of our satellite for billions of years. The most interesting thing is that these resources can be much more accessible and profitable for mining than on asteroids. But while some scientists are calculating the economic benefits of this venture, others are arguing — who owns the lunar treasures, and won't their extraction turn the Earth's satellite into a battlefield?

The dream of mining beyond the Earth has been in the air for decades. At first, these were just scientific projects, mostly hypotheses. Then real developments appeared, proposed by commercial companies that caught fire with the "asteroid fever".

All these companies pursue the same goal — rare and expensive platinum group metals : ruthenium (Ru), rhodium (Rh), palladium (Pd), osmium (Os), iridium (Ir), platinum (Pt). These are critical elements for electronics, medicine, and green technologies. In addition, the extraction of water, a potential fuel needed for deep space missions, is also being considered.

The content of platinum group metals in the Earth's crust is low, but there are many of them on asteroids. At least, this is indicated by the results of meteorite analyses and direct measurements taken from spacecraft.

Scientists are particularly focused on near-Earth asteroids, which are theoretically easier to reach than the Moon or the asteroid belt. There are two types of interest: Class M asteroids and Class C asteroids.

The former are considered fragments of the cores of dead protoplanets. Such bodies have a moderately high albedo, and their spectrum indicates the presence of a high proportion of metals — iron, nickel, and, most importantly, platinum group metals that are "dissolved" in the asteroid material.

The second is dark carbonaceous objects containing hydrated minerals (for example, clay, gypsum). Water molecules are "trapped" in the crystal lattice of these minerals, that is, they are embedded inside the crystal. Such asteroids are considered as potential sources of water for future space bases and interplanetary refueling.

However, it is very difficult to understand how many near-Earth objects people can actually reach with current technologies in order to start mining. In 2014, astrophysicist Martin Elvis proposed a special mathematical method for such an assessment. The scientist's conclusions have cooled the ardor of many. According to his calculations, there are 10 asteroids with platinum group metals available to mankind, and 18 water—bearing ones. A very modest "cosmic harvest", taking into account hundreds of billions of dollars of investments.

While some scientists were dreaming of passing asteroids, others decided to look at their feet — more precisely, at the surface of the nearest large celestial body to us. It's about the moon.

An international team of astronomers led by Jayanth Chennamangalam, an independent researcher from Canada, asked the question: what if the main space treasures have long been on the Moon thanks to the same asteroids that bombarded the lunar surface for billions of years? The researchers presented their findings in an article published in the journal Planetary and Space Science.

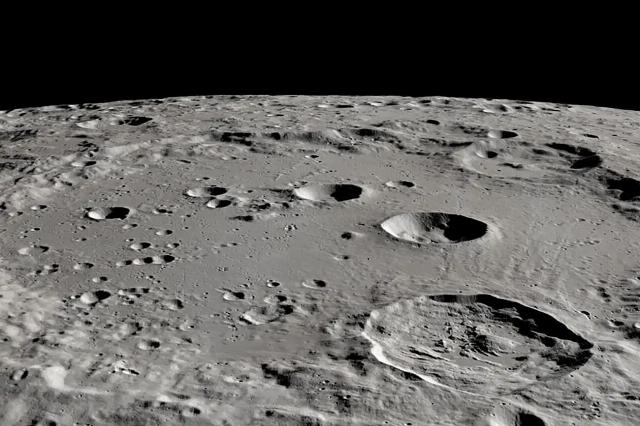

Webb Crater is a small impact crater in the northeastern part of the Sea of Plenty on the visible side of the moon. A snapshot of the Lunar Orbiter–I probe

Image source: NASA

Previously, scientists were sure that when an asteroid crashes into the lunar surface at high speed, it almost completely evaporates. Only small fragments may remain of it, but they scatter in different directions and mix with the lunar dust. Collecting such material is costly and unprofitable. It's a waste of time and money.

But the authors of recent studies paint a different picture. Complex computer simulations have shown that under certain conditions, usually with "vertical" impacts, a significant part of the asteroid can survive. Especially their metal core. As a result of the formation of large craters, such material often "drains" into the center. If a small depression appears from the impact, the material mixes with the breccia, a caked mass of debris that fills the crater bowl.

In other words, such formations on the Moon become not just "funnels", but natural "containers" of minerals. It turns out that Class M asteroids could have left behind deposits rich in platinum group metals, while Class C asteroids could have left behind deposits of hydrated minerals, that is, water.

But how many such natural "containers" actually exist on Earth's natural satellite? To answer this question, Chennamangalam and his colleagues studied 1.3 million lunar "craters" and based on the information received, created a model that included data on the frequency and types of impacts, the probability of "survival" of the material and its concentration in the craters.

Calculations have shown that there may be almost 6,500 craters on the Moon with a diameter of just over a kilometer, formed by metallic asteroids with a high content of the platinum group. In addition, there are just under 3,400 craters with a diameter of more than a kilometer, which appeared as a result of the impact of dark carbonaceous asteroids with hydrated minerals.

The figures obtained are an order of magnitude higher than Elvis' most conservative estimates of near-Earth objects that can be reached. Simply put, there are potentially many more craters with rare metals and water on our satellite than there are asteroids rich in these minerals available to human technology.

The Chennai team estimates that the lunar craters contain more than a trillion dollars worth of platinum and other precious metals.

"Mining on the moon is much easier than on asteroids. Firstly, most of these objects are much further away than our satellite. Secondly, gravity is very weak there, which creates technical difficulties for landing vehicles. By contrast, the moon's gravity is only six times weaker than Earth's. In addition, people have landed many more vehicles on the surface of the satellite than on the surface of asteroids. That is, there is experience," explained Chennamangalam.

However, even if mining on the moon is technically easier, it may be more difficult from a legal point of view. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 remains the cornerstone of international space law. It sets the rules for all types of activities off-Earth, including the extraction of space resources. It explicitly states (article II):

"Outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation either through the proclamation of sovereignty on them, or through use or occupation, or by any other means."

The problem is that the contract can be interpreted ambiguously. On the one hand, it prohibits the "national appropriation" of space, on the other hand, it does not specify the status of private companies. In this case, should private mining be considered a "national appropriation" or an independent activity?

Many experts agree that there are gaps in the agreement. In particular, he does not explain how commercial activities should be regulated, who can own space resources, how to share profits, and how to protect the environment.

"Some experts compare mining on asteroids with fishing in international waters. They say the sea is nobody's, but you can fish. However, this analogy is poorly applicable to the Moon — the scale is too large and the consequences are too serious," explained Rebecca Connolly, an Australian lawyer from the University of Sydney.

Representatives of the international space agencies are trying to find a compromise. It is for this purpose that the so-called "Artemis agreement" was proposed in 2020, allowing the commercial use of space resources. It is based on the Outer Space Treaty of 1967. However, only 55 countries have signed it, but Russia and China, the two leading players in space, have not joined them.

It turns out that the legal uncertainty regarding the exploration of minerals on the Moon remains. If a private mission goes to our satellite for this purpose, without clear legal rules, this can create a number of precedents, including possible conflicts. Experts agree that the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 needs to be finalized, like other similar documents, and all existing gaps in them should be eliminated.

Igor Baydov