To facilitate the survival of people after an atomic war, it is rational to create seed stocks that allow harvests to be restored even after years of failures caused by a nuclear winter. Otherwise, researchers from the United States believe, it will be problematic to provide food for the survivors.

In a new scientific paper published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, researchers from the United States have tried to calculate what the consequences of a nuclear winter will be for agriculture. They came to the conclusion that they can be somewhat mitigated if they prepare for such events in advance. The authors considered the motive for the preparation to be "current geopolitical tensions" such as the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, the smoldering conflict in Kashmir and instability in the Middle East, which "jeopardized the fragile deterrence that dominated the last years of the cold war" and the fact that "the risk of nuclear war has increased."

To calculate the consequences of different variants of nuclear war, we took the agroecosystem Cycles model and based on it we tried to calculate changes in the corn harvest at 38.5 thousand points on the earth's surface in seven scenarios. One of them was without a nuclear war, six more were with a nuclear war of various scales, from five million tons of soot thrown into the stratosphere (the weakest option is the India—Pakistan conflict, no more than 27 million victims), to 150 million tons (the Russia—NATO war, up to 360 million victims, apparently the authors they were based on outdated data on the Russian nuclear potential).

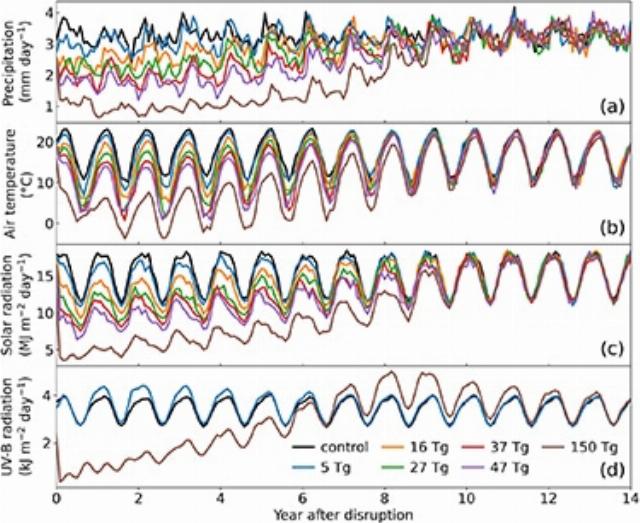

In this simulation, after soot emissions from burning cities into the atmosphere, precipitation, air temperature, and solar radiation immediately decreased dramatically. In the most devastating scenario of a nuclear winter, with the release of 150 million tons of soot, precipitation and solar radiation worldwide fell by 70 percent, and air temperatures dropped by more than 15 degrees Celsius for several years after the outbreak of war. In addition, the soot heated the stratosphere in which it was located, which caused depletion of the ozone layer.

After some time, the soot settled in the simulation, but the ozone had not yet had time to accumulate, which led to an increased level of UV radiation. In the scenario of a Russia—NATO war, the level of ultraviolet radiation on the planet's surface in 8-10 years significantly exceeded normal values.

The drop in corn yields in this latter case is very significant: in fact, in the first four years, its harvest was zero, with the exception of the warmest tropical regions. Therefore, the global harvest decreased fivefold. Even in the case of a minimal—scale atomic war (the weakest is the Pakistan-India war), the drop in yields reached nine percent, although it hardly affected the United States. Full (more precisely, up to 95 percent of the norm) crop recovery in the biggest war happened only after 12 years, in the weakest — after seven years.

Monthly fluctuations of key meteorological variables for the average corn growing areas after the nuclear war. There are different options from 5 teragrams (5 million tons) of soot to 150. Parameters: (a) precipitation, (b) temperature, (c) insolation, (d) ultraviolet. A year is defined as the period from May 15th of one year to May 15th of the following year

Image source: Armen R Kemanian et al.

The researchers noted that some of the problems after the conflict can be mitigated if warehouses with corn seeds are created and distributed around the world in advance. The fact is that different lines of these plants produce the maximum yield at different air temperatures. Taking into account the possibility of an atomic war, it is possible to pre-place warehouses with more "cold-loving" seeds in places where the climate is warm now.

Then, after a nuclear winter, the seeds there will give more returns than if there are no such warehouses, and more thermophilic corn lines will be sown. The scientists named such seed stocks the Agricultural Resilience Kit (ARK) and called for their deployment in advance. With a weak nuclear war, they will increase yields in the post—war period by 1.1 percent, and in the case of the strongest - by 10 percent. This, as the authors of the study suggested, "will save many lives."

Naked Science previously wrote in detail why physicists sharply criticize the idea of a nuclear winter as unscientific. In reality, nuclear strikes, even in Japan, did not lead to fires in Nagasaki, and in Hiroshima, where they were, fires caused coals from braziers on which food was then cooked, scattered among the rubble of houses made of wood and paper. In addition to the fact that such fires are technically impossible in modern cities (due to other building materials), all known fully anthropogenic (non-forest) fires do not produce soot capable of reaching the atmosphere. And it is quickly washed out of the troposphere by rains, which excludes a nuclear winter.