Astronauts during space flights often experience problems with the normal functioning of the immune system, skin itching, and inflammation. The authors of the new scientific paper believe that the reason is to try to keep the station as germ—free as possible. They offered to fix this situation.

From the very beginning of space flights, the insides of ships and orbital stations were sterilized: otherwise, they believed that the proliferation of microbes in space could pose a threat to humans. One of the problems with this strategy is that it has never worked effectively enough. Most of the cells in the body do not belong to us: they are bacteria and archaea that consistently coexist with the human body.

With an acute shortage of normal "extrahuman" microbes on the orbiting stations, some of these "intrahuman" bacteria and archaea begin to live on the surface of the stations and in its life support systems, creating serious microbial contamination of a type that is not found on Earth. After all, on the surface of the planet, the "human inhabitants" have no freedom to colonize the surrounding space: all places are already occupied by "wild" bacteria, better adapted to life outside of us.

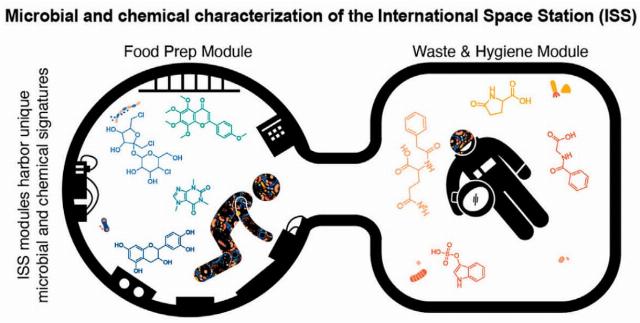

However, the authors of the new work at Cell have shown that the "keeping the station sterile" strategy has another problem. They examined 803 swabs from the ISS — 100 times more than they usually took for previous studies — and then compared their microbial and chemical diversity with terrestrial samples from cities.

On the ISS, almost all types of microbes found on the walls originated from human skin. The concentration of disinfectants and cleaning agents was uniformly high throughout the station. There were also differences: the areas where food was cooked and taken contained more species capable of living on human food. The "toilet" modules contained more microbes found in feces and urine (however, in our homes the picture is similar in this sense).

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria from the ISS

Image source: NASA

Similar brushstrokes taken on the Ground were completely different. The diversity of microbes there was much higher. The only people who were similarly poor were swabs from large hospitals and clean city apartments. There were also more bacteria living in soil and water in the terrestrial samples. This is quite important, because they are often biologically "neutral" to humans, which cannot be said about people living outside of a person from his own microbiome. If the human carrier itself is well adapted to them, then other people on board the ISS are often no longer there.

The researchers propose to deliberately bring soil and aquatic bacteria from Earth aboard the ISS. "There's a big difference between being exposed to healthy garden soil or languishing in your own sewage. Meanwhile, something like this happens when you are in a strictly closed environment where healthy sources of microbes from the outside do not enter," the authors noted.

An additional factor: the growth of microbial diversity reduces the likelihood of asthma and allergic reactions. However, pointing out this, the authors cautiously noted that microbial diversity does not always reduce the frequency of allergies in animal experiments, but still considered this factor important. In other words, they are largely supporters of the "hygiene hypothesis," according to which the widespread spread of allergies in people with a modern lifestyle is the result of excessive sterility in their homes, which are regularly treated with disinfectants. The ISS, the scientists noted, is an extreme example of such processing, potentially one of the least safe.

Probably, the authors' approach has already been tested in practice, however, during the ground testing of space flights. In 1972-1973, the BIOS-3 experiment was conducted in the USSR, during which three people did not leave a sealed and gas-enclosed unit for 180 days. In terms of the size of the block, the duration and the number of participants, the experiment corresponded to a flight to Mars in a "Heavy interplanetary ship", which was designed at the Korolev Design Bureau back in the 1960s. Back then, people grew wheat and a number of other crops in a mini-greenhouse, then eating the products from the grown plants.

Alexander Berezin