One of the problems of people in zero gravity remains the rapid degradation of tissues, without which active activity or even simple walking is difficult, such as cartilage in the knee and hip. Scientists have found a way to seriously improve the situation with minimal time expenditure.

In the coming years, people will return to the moon, and within a dozen years they will try to land on Mars. If everything is clear with the first one and, judging by the experience of the 1960s, it is quite feasible, then with the second one it is more difficult. A number of scientific papers have shown that astronauts on the ISS degrade the cartilage covering parts of the bones in their knees quite quickly. In terrestrial conditions, prolonged thinning of such cartilages results in osteoarthritis and often complete inability to move independently due to acute pain.

Of course, on the ISS, cartilage thinning occurs at zero gravity, while on Mars it is equal to 0.38 of Earth's. Nevertheless, concerns remain. What if, after a three-month flight to the Red Planet (which is exactly the trajectory SpaceX is planning), it becomes difficult for an astronaut to move due to the reduced thickness of cartilage in his knee?

Researchers from Johns Hopkins University (USA) conducted a nine-week experiment on laboratory mice to prevent such situations. They described the results of their work in the journal npj Microgravity.

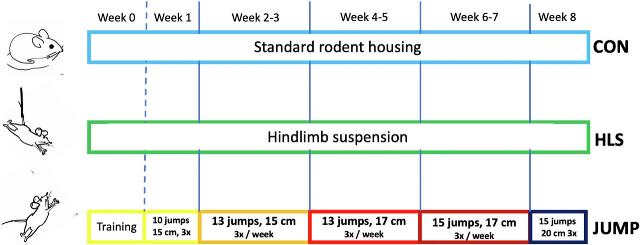

The scientists divided the mice into three groups: one was restricted from moving around — the rear part of the body was suspended so that the animal could not rest its hind legs on the floor. The other was placed in a special machine (pictured), where the mice had to jump very smoothly with increasing difficulty. The third group was a control group.

To motivate the rodents, the researchers trained them to jump at the blink of a green LED. To do this, after he blinked, a current was applied to the floor in the "jumping apparatus" — at first weak, then up to 175 volts. The animals realized almost immediately that they had to jump up (onto a platform with a different floor, where no current was applied) after the LED signal and even before the current was applied.

The authors trained mice according to the popular scheme of progressive increasing overload

Image source: Marco Chiaberge, Johns Hopkins University

Nine weeks of the experiment is equivalent to about five years of human life. By the end of this time, the thickness of articular cartilage in the legs of the suspended group decreased by 14% compared to the control group. For the group of jumpers, on the contrary, it increased by 26%.

In addition, although this was not the purpose of the experiment, the jumping group seriously strengthened their bones: the tibia showed 15% higher mineral saturation than the control group. The spongy bone tissue at the ends of the paw bones became significantly thicker and stronger than in the control group. It is she who absorbs the shock load during jumping and running.

The very small training volume in this work is noteworthy. The mice jumped 10 times per workout (by 15 centimeters), and only three times a week. By the end of the experiment, 15 times (by 20 centimeters), but still only three times a week. It usually takes a lot longer for a person in space (and beyond) to train. For example, astronauts on the ISS spend at least two hours a day on the simulator, otherwise their muscle and bone mass will decrease rapidly. Then, upon returning to Earth, they will be like the cosmonauts of the Soyuz-9 mission, who, after 18 days of flight in a cramped ship (where there is no room for simulators), could not walk to the bus on their own.

The average daily time spent on exercise in rodents was measured in a matter of minutes. This is a very short training time, but it turned out that it has a strong effect on strengthening cartilage and bones.

Image source: Marco Chiaberge et al.

From their experiment, the scientists concluded that it is necessary to adapt jump training for astronauts. Moreover, it is worth starting such a program months before space flights. It is necessary to create a compact space jumping apparatus for people to train in flight. It is possible that such a device will reduce the total time required for astronauts to train today. This will be especially valuable on the Moon and Mars, where people's time will be extremely busy. Similar workouts, although in a modified format, may be useful for patients with osteoarthritis (in the initial phase) on Earth, the authors of the new study believe.