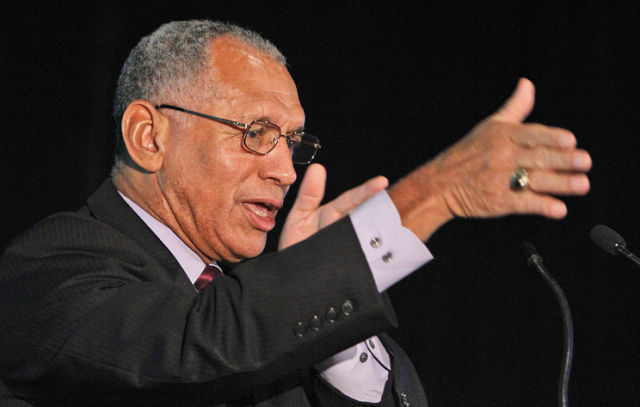

Former American astronaut, head of NASA in the Barack Obama administration (2009-2017), Major General of the US Marine Corps Charles Bolden, in an interview with TASS, assessed the prospects for cooperation between the United States and Russia in space exploration, shared memories of a joint shuttle flight with Sergei Krikalev in 1994, commented on plans for landing people on the Moon and Mars.

— Your last space flight was the STS—60 mission in 1994. You flew with Sergei Krikalev, who was the first Russian cosmonaut to travel on the Space Shuttle. Tell us about your impressions of that flight.

— Initially, I did not want to participate in this. At that time, I was in Washington, I had three space flights under my belt, I worked as a deputy assistant to the head of NASA at the headquarters of the department. I didn't like it at all, I had to deal with Congress and everything, and I really wanted to go back to Houston. The NASA administrator suggested that I fly into space again. I agreed, saying that I liked the idea, in the hope that I would be appointed commander of the Hubble Space Telescope maintenance mission (Bolden piloted the Discovery shuttle, which launched Hubble into orbit in April 1990 — approx. TASS). But I was told that the crew for this mission has already been recruited. When I asked what they were up to, they mentioned two Russian cosmonauts, after which I said: "Stop! I don't want to fly with the Russians. I'm a Marine, and I've been trained all my life to kill them, and they were taught to kill us, I don't want to fly with them." But I was asked to calm down and informed that the Russians would have dinner with my friends in the evening: "Why don't you meet with them and come back to this conversation the next morning." That's what I did.

When I arrived, Sergei was already there — a good-looking young engineer, not a military man, who speaks English fluently. I introduced myself, and he introduced me to Vladimir Titov, who spoke absolutely no English. We sat down to dinner, and our whole conversation was about families, children, and so on. By the end of dinner, we realized that we had a lot in common. All three of us wanted a bright future for our children, to make the world a better place than it was then. Therefore, I fell in love with them, and the next morning I came and said that I had changed my mind and was ready to fly. That's how I was appointed commander of the STS-60 crew.

I learned a lot from both of them, but especially from Sergei, since I had the opportunity to fly with him. And although I've had more flights than Sergei, he's spent a lot more time in space than I have. After all, we flew only on shuttles, we considered the mission to be 16 days or so long, whereas his shortest mission lasted four or six months at the Mir station. That's why he gave me a head start on long-term space flights. At the time of our joint training, Vladimir spent 366 days at the Mir station, and also participated in a mission during which the Soyuz capsule with the crew was shot off from the launch vehicle due to a fire. So they had much more experience than I did, and Sergey turned out to be an excellent mentor who was very comfortable in space. By that time, I had also flown, so I also felt comfortable in space. But he had his own way of navigating the spaceship. We exchanged a lot of ideas about how the Russian space program works, about how we work. So we both had to adjust to the way our systems work.

— Speaking of Russian and Soviet cosmonauts. Yuri Gagarin would have turned 90 this year. Could you tell us what his name means to you personally and to the world? What lessons has NASA learned from Russia's rich experience in space exploration?

— Despite the rivalry between our countries, we were all incredibly proud and glad when Yuri Gagarin became the first person to go into space. At the same time, as Americans, we were somewhat disappointed that we were not there first. We were in a hurry and tried our best to prepare Alan Shepard (1923-1998) for launch.

But Gagarin paved the way. After one of the launches, I visited Moscow and realized how much he was revered there, what an impact he had on the space program, on customs and traditions. He is a kind of hero for everyone in the world of space.

For us, he set a bar that we wanted to surpass as much as possible. And when we finally sent Alan Shepard into space, we were incredibly happy. And then John Glenn flew around our planet. It was great.

— You mentioned how tense relations between the United States and the Soviet Union were during the Cold War. But in the 1990s, the United States and Russia became partners in space exploration. Now there is a cross—flight program that allows Russian cosmonauts to fly into space on American ships, and NASA astronauts to fly on Soyuz. How do you assess this program, what does it mean for bilateral relations and what is its future? It is planned to continue work until 2025 inclusive, but nothing is known about further plans yet.

— You said about establishing relations in the 90s, but in fact it all goes back to 1975, to the Soyuz-Apollo project. That's what no one expected! The meeting of the Soviet and American crews in space, hugs after opening the hatches between Tom Stafford and Alexei Leonov, who became friends forever. This is what set the tone for further relations. Fate separated us for a while, we didn't do anything together, because we were engaged in the Space Shuttle program, and the Russians, then Soviet cosmonauts worked at the Mir station. But we were trying to find a way to join forces again.

As you know, my final mission on the shuttle, STS-60, was planned as a test, a test, the purpose of which was to understand whether it was possible to prepare Russian and American crews together to fly on the same ship. But, more importantly, whether our support teams can cooperate. This was the first stage of the Mir—Shuttle program.

Our flight was successful, and the training program was transformed so well that NASA was able to send Americans to Mir. And subsequently, we managed to send eight American astronauts to this station. And then we began to get closer thanks to President Bill Clinton (1993-2001) as a coalition of space agencies with the aim of creating an International Space Station.

By that time, we had actually concluded a deal to create the ISS with four partners. And he instructed to start over, because he wanted Russia to participate in the ISS program. Therefore, they returned to the drawings, opened the possibility of signing the contract and involved the Russian space agency. The rest is history.

I always say that space is an incredible environment that allows nations to come closer together in the name of a common goal. The reason why Roscosmos and NASA get along so well, in my opinion, is that we have common goals and ambitions. We understand what teamwork is and what it means to earn each other's trust. Something that our governments have not yet come to. But I think work is underway on this.

— Returning to the question of cross-flights. What, in your opinion, is the future of this program?

— I hope we will continue to do what we are doing. I am one of those strange guys who hope that at some stage we will involve the Chinese in this cooperation, who could also become our space flight partners. The life of the ISS is coming to an end, and our hopes for the future are linked to commercial space stations. We have companies like Axiom, Blue Origin and a number of others that are building commercial space stations. Therefore, it would be great to have the opportunity for a crew from any country to go to a commercial space station and do what they need there.

It would be good to be able to use the Chinese Tiangong orbital station as such a platform. It is relatively new and could become an international platform, as the ISS is today. But for this, it is necessary to be able to meet, sit down at the table and talk in the same way as we managed to do with the Soviet Union and Russia and what led us to what we have today.

— Russia is also working on its own orbital station project. What do you think of him?

— I hope that whatever Roscosmos produces, it will stand on a par with other international devices that can use everything. I don't know if such a task is being set, I don't know much about it. I am convinced that if we really want to explore space beyond low Earth orbit, as we claim, then we need several orbits at different angles of inclination, on which different vehicles, including unpiloted ones, would be placed. With the help of robots, we would deliver materials for experiments to such platforms, they would be in low-Earth orbit for a month, a year, or as long as necessary. Then we would pick them up ourselves or send robots to do it.

But there would also be crewed platforms on which, for example, biomedical research would be conducted. This will happen on American commercial platforms. And I hope that, whatever the Russian platform turns out to be, it will be offered for international use for similar purposes.

— On the issue of cooperation between Russia and the United States in space, how do you assess the current situation? What has changed since you headed NASA?

— There is much more tension today compared to the time when I flew into space with Sergei. Then our partnership, if I may, was on the rise. Now, at a time of diplomatic tension between the United States, Russia, China, Iran and all the others, at a time when governments are in conflict, both space agencies — NASA and Roscosmos — are trying to maintain a partnership, the benefits of which they have no doubt for the world. Therefore, returning to your previous question, I hope that we will continue cross-flights, astronauts will continue to fly with us on American ships, and we will continue to fly on Soyuz, thus getting to certain platforms. I think this is of key importance.

I am one of those who is sure that in order to get to where I would like us to get, for example, to Mars, international cooperation is necessary. Going into space is very difficult. It is really difficult to go to the moon, for example. It is even more difficult to talk about sending people to Mars. Although there are many individuals and countries who want to be the first to get there, I am convinced that this will be achieved only if there is cooperation between States, scientists and private companies. Let's see who turns out to be right.

— In the context of international tension, the issue of cooperation on the ISS remains important. What do you think about this? Most of the States participating in the project have committed to extend the operation of the station until 2030.

— As far as I understand, everyone has agreed to work until 2030, and frankly, in my opinion, this is sad. I hoped that we would retire the ISS, if not next year, then at least by 2028. But for this, it is necessary that an alternative platform be ready to receive the crew. It is necessary to be able to ensure a smooth transition from the ISS to affordable commercial vehicles. What we definitely don't want is a repeat of the gap in the transition from the Apollo program to the Space Shuttle program or from the Space Shuttle to the commercial cargo and manned ships available today. Such a gap should not be allowed.

To achieve this, commercial enterprises need to prepare, test, test and certify their devices so that we can begin transferring operations from the ISS to these commercial platforms. And it will probably take time until 2030.

The decision that the life of the ISS has come to an end will be made either by us or by Mother Nature herself, because this is a mechanism, and some of its elements are beginning to fail, and it is becoming more and more expensive to maintain and maintain its operation. If the life of the plant is completed before we decide, then there will be a gap. And I hope that doesn't happen.

— My next question also concerns the difficult relations between our countries. Deputy Secretary of the US Air Force Melissa Dalton recently said that the United States intends to put hundreds of satellites into low Earth orbit to counter Russia and China, in order, in her words, to deprive them of "the advantage of a pioneer." What does this mean in your opinion? Does this mean that we have entered the era of the Cold War in space?

— I try not to talk about these topics. I am a military man, a retired Marine Corps Major General. But my time has passed, I do not have access to the information on the basis of which she makes such statements. I do not know the capabilities of our allies and our rivals.

As the diplomat that I consider myself to be, I do not give up hope of leading us all to discuss how we can achieve what we are striving for.: How do we work together to get people to Mars without starting a war?

Because in the event of a conflict in space — especially with the use of kinetic means — as soon as you shoot down a satellite in space, you lose your orbit. This is not the same as shooting at someone or blowing up a tank on the surface of the planet, resulting in a pile of debris that can simply be bypassed. It won't work that way in space. I know that everyone knows this and everyone is thinking about it. We all need to understand that this will deprive us of the opportunity to engage in space for a while. It all depends on where it happens, at what altitude, in what orbit. After all, this orbit will be impossible to use because of the debris.

I didn't answer your question because I don't know the answer. I am a constant optimist. And although I am a military man, my task was to do everything in my power to maintain peace and prevent war. I knew that if I had to put into practice what I had been taught, that is, to fight, it would mean that at some stage we had failed. Despite the fact that I am a military man, I am also a diplomat. And I have devoted most of my 34-year career in the Marine Corps to negotiations, cooperation and training people to prevent war, and this remains my task. I did the same thing as the head of NASA.

— Could you tell us more about the Artemis lunar program? There have been many postponements, so far only the first stage of the mission has been implemented — Artemis-1.

— That's right. The launch of Artemis-2 may take place as early as September 2025 or closer to 2026. But this is typical for the space program of our country and, I believe, other countries. We set goals that we want to achieve, but something is happening either with financing or with supply chains.

Considering all that has been done, I would call it very successful. If we measure success by meeting deadlines, then, of course, we did not succeed, because we are years behind the schedule we expected. And here we need to catch up.

The US Congress will not endlessly allocate funds, we already saw this last year, in the budget for the current year. We had programs that were delayed, the implementation of which took longer than expected, and Congress finally said it would not continue to fund them.

— Artemis is actually laying the groundwork for sending humans to Mars. Given the delays and non-compliance with the schedule, do you still expect that the landing of people on the Red Planet will take place in the 2030s?

— I will stick to my goal of landing people on Mars in the 2030s. It's getting harder and harder to do this. And I heard that my friend, the head of NASA, Bill Nelson, mentioned the early 2040s. But I will keep hoping.

We would have done this without any problems, I think, in the mid-2030s, if the program had progressed at the same pace as it did after I left the position and James Bridenstine (former head of NASA (2018-2021) — approx. TASS). It seemed that we were moving at a relatively good pace, and then everything started to slow down a little. Boeing and other companies had problems. But I think we can do it.

— And what is the role of private companies in sending people to Mars?

— I don't think private companies can do this alone. I will return to what I said earlier, about the key importance of cooperation between countries, scientists and industry. It's the only way we'll get to Mars.