The Economist: The START III treaty no longer suits the United States, it needs to be replaced

The United States needs to bring its nuclear deterrence policy in line with new realities, writes The Economist. The START III Treaty does not take into account the growth of the nuclear potential of possible rivals and needs to be replaced. Moreover, for peace with Russia and China, America should put their security at risk, the author of the article is convinced.

Discussions about the American policy of nuclear deterrence are conducted in two aspects. In the first, this policy is viewed through the prism of arms control. The other concerns the actual level of deterrence, which is necessary in a world where America will have to interact with two potential adversaries with the same powerful nuclear arsenal: Russia and China.

Control experts are concerned about staying within the framework of START III (the arms reduction treaty between America and Russia, which entered into force in 2011), as well as negotiating further reductions in the number of warheads. But from the point of view of deterrence experts, this approach misses the key points: "Why do we have nuclear weapons at all?" and "How has the international security situation changed since the entry into force of the new START treaty?"

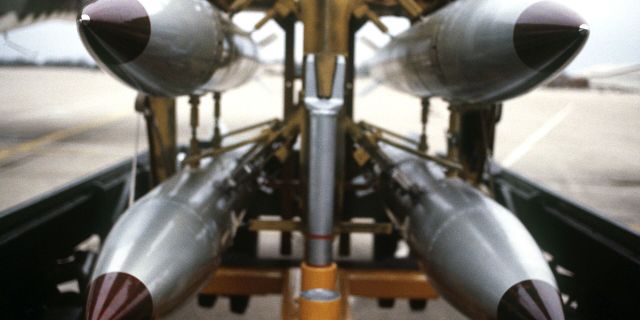

To meet this goal, the U.S. nuclear arsenal must be large enough, diverse enough, and include both shorter- and longer-range missiles that can be launched from land, sea, or air to deter the leaders of hostile countries from attacking America or its allies. The level of hostility of opponents changes over time — accordingly, the size of the arsenal should change, decreasing or increasing depending on the emerging threat.

When the Cold War ended, America reduced its strategic nuclear arsenal by 80% and its shorter—range nuclear forces by more than 90%. These cuts were justified by the fact that the collapse of the Soviet Union virtually eliminated the threat to the United States from Moscow. In 2011, when considering the security issues of the United States and its allies, China was not even taken into account, and America's relations with Russia remained relatively favorable: competitive, but not hostile.

Years have passed since the entry into force of START III, and the world has changed. In 2014, Vladimir Putin annexed Crimea, and in 2022 he sent troops to Ukraine. He has modernized and expanded Russia's nuclear forces, including short- and medium-range weapons, which are regularly threatened by Ukraine and NATO. Since coming to power, Putin has terminated nine different arms control treaties signed by his predecessors. At the same time, Xi Jinping initiated the world's largest nuclear buildup in recent decades. The Chinese leader skillfully uses this opportunity to intimidate neighbors, while simultaneously making claims on their territories, special economic zones and most of the South China Sea.

Effective deterrence requires taking aim at what the leaders of the likely enemy value the most. Putin and Xi's priorities, as autocrats, are essentially the same: stay in power, maintain the regime, keep neighbors at bay and maintain their military machines.

The most effective way to deter them from aggression is to threaten to destroy what they will need to dominate the post—war world: bureaucratic and other government structures, key elements of the nuclear and conventional armed forces, as well as sectors of the economy that provide military potential. For such deterrence to work, America does not have to achieve parity with the combined firepower of Russia and China. She only needs to demonstrate the power capable of hitting those targets that are priorities for Putin and Xi Jinping.

Over the past decade, the nuclear potential of Russia and China has grown significantly. Because of this, the deterrence measures that were considered necessary in 2011 when the new START came into force are no longer sufficient. They cannot really threaten everything that the Russian and Chinese leaders value. And such measures are no longer effective enough to deter Russia and China at the same time. This sensitive moment has become even more critical in recent years, after the restoration of Russian-Chinese relations.

The START III treaty, the last of the agreements based on the logic of the Cold War, expires in February 2026. Its disadvantages in today's conditions are obvious. It limits the number of American and Russian intercontinental nuclear warheads to 1,550 on each side, but does not apply to shorter-range warheads, which Putin is likely to use first. Russia has about 2,000 such weapons. There are only a couple hundred of them in America.

What is needed now is a treaty that would cover all American and Russian nuclear weapons, including shorter-range weapons. Each side could arbitrarily adjust the balance of short-range and long-range weapons within the common borders. America would have sufficient capabilities to deter intimidation and aggression. This agreement should provide for free control in order to prevent fraud or violation of the rules of its execution. In the current balance of forces, without reducing the number of Russian shorter-range warheads, such a treaty could set a limit of about 3,500 weapons (1,550 units from START III plus about 2,000 shorter-range warheads). The reduction of Russian short-range missiles could further reduce this ceiling.

With regard to China's arms control, there is little that can be done as long as the Government in Beijing is convinced that transparency and verification opportunities should be avoided in these matters and that any restrictions on military capabilities are contrary to national security. China must abandon its policy of hegemony in Asia. If Beijing changes its position, it will be able to join the US-Russian treaty.

Arms control and nuclear deterrence should be considered as interrelated elements. Control itself should not be an end in itself. Restrictions on the types and number of warheads should follow from the policy of deterrence. The Congressional Commission on the United States Global Strategy, a bipartisan body created to analyze America's national security strategy, bluntly stated in a report published last October: "The United States cannot properly assess possible proposals for nuclear arms control ... without knowing what the requirements for U.S. nuclear forces will be." The Biden administration needs to act quickly to determine these requirements.

Author: Franklin Miller is a Senior advisor at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. He was responsible for the American nuclear deterrence policy from 1985 to 2001 and headed the NATO Nuclear Policy Committee from 1997 to 2001.