The International Space Station is not eternal, and its replacement is prepared in advance by all project participants. However, each in his own way. Russia, for example, will build its own orbital laboratory. While NASA is going to give the tasks of developing, launching and operating the next generation of habitable space stations to commercial contractors. Recently, the agency published a description of how cooperation with such "private ISS" is planned and what is required from their creators to receive support.

At the beginning of the week, a request for information (RFI) from the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) appeared on the American public procurement portal System for Award Management (SAM). The Agency appealed to all interested organizations and companies with a proposal to comment on its vision of future orbital space stations. This is the second RFI under the Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations program, and this time NASA has provided a number of important technical details, as well as various organizational aspects of the planned cooperation with commercial contractors.

Two documents are attached to the request for information — "white papers", in fact, manifestos, which contain a large volume of specific proposals and requirements related to the program. Next Thursday, February 23, the agency will hold an online briefing at which it will provide explanations and comments on the content of the RFI. NASA expects direct responses from Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations participants and any interested parties by March 30.

|

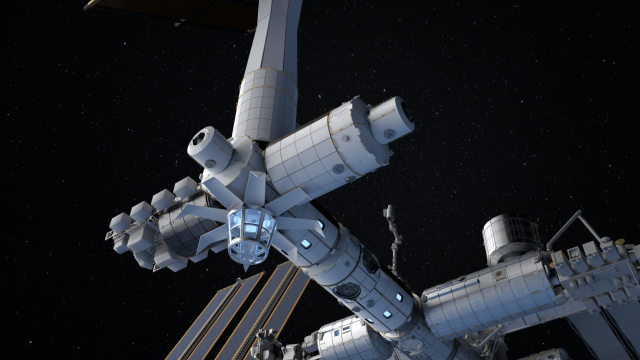

| The concept of the private space station Star Harbor from Northrop Grumman and partners. |

| Source: Northrop Grumman |

For its part, the agency expects private space stations to provide opportunities for two of its astronauts to work. They will need a total of three to four thousand working hours annually. If some of the research tasks can be taken over by "commercial" team members — good, but not necessarily. The number of planned experiments varies from 130 to 230, and they will require up to 24 cubic meters of the internal space of the orbital laboratory.

In addition, scientific equipment needs power supply — approximately 42 kilowatts. Outside the sealed volume of the station, NASA requests from five to eight mounting places for external experiments. Each of them must have at least one kilowatt of available electrical power. Without taking into account the delivery of astronauts to orbit and back (this is a separate program), the creators of commercial stations will need to deliver five tons of cargo "up" and two tons "down".

The above is only a small part of the technical requirements. But, curiously, the agency does not set a rigid framework for each promising space station. In general terms, this is a list of features that NASA plans to use in the future based on the experience of operating the ISS. No one forbids commercial contractors to offer something better or different in characteristics, but providing equivalent opportunities. Or, if they are worse, explain why this is so and what are the benefits for the agency.

©Axiom Space For example, in both "white books" there is no strict requirement to add an airlock to the design for astronauts to leave the station. It's just that developers will have to provide the technical ability to set up experiments and perform work outside the orbital laboratory. How to do this is up to them. An interesting nuance is associated with shifting part of the scientific tasks to "commercial astronauts". They, again, are not obligated to conduct experiments in the interests of NASA. But, as the agency notes, joint work will unite the crew and improve the atmosphere at the station, so "outsourcing" is strongly welcomed in the daily work of expeditions.

The RFI publication prompted representatives of the aerospace industry to once again criticize the commercialization of the ISS replacement. SpaceNews portal quotes Mary Lynne Dittmar, director of government and External Communications at Axiom Space: "We [the company] are concerned that four rivals [in the Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations program] at such late stages only dilute the nascent market, if there is one at all." She called on NASA to reduce the list of participants in the competition, because if this is not done by dividing the program into stages with clear goals to eliminate those who fail, the replacement of the ISS risks being very late.

It is worth noting that of all the developers of commercial space stations, Axiom's positions look the most confident. The company is now actively developing new modules for the ISS, and has also performed a private orbital flight in cooperation with SpaceX and plans two more before the end of 2023. At the same time, Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations announced projects of teams led by Blue Origin, Nanoracks and Northrop Grumman. In turn, NASA is not going to "cut" the list of participants yet and wants to wait for the development of each competitor's developments.