The Reuters agency has published interesting material-the investigation of Joel Schectman, Bozorgmehr Sharafedin "America's Throwaway Spies: How the CIA failed Iranian informants in its secret war with Tehran" ("American one-day spies: How the CIA failed Iranian informants in the secret war with Tehran"). Our blog offers the first part of the translation of this material.

Map of Iran's nuclear facilities for 2020 (c) by the IAEAThe spy was minutes away from leaving Iran when he was captured.

Gholamreza Hosseini was at the Imam Khomeini Airport in Tehran at the end of 2010, preparing to fly to Bangkok. There, an Iranian technology engineer met with his handlers from the US Central Intelligence Agency. But before he could pay the exit tax, the ATM at the airport rejected his card as invalid. Moments later, a security official asked to see Hosseini's passport.

Hosseini said he was taken to an empty VIP lounge and told to sit on a couch facing the wall. Left alone for a few dizzying moments and not seeing any surveillance cameras, Hosseini reached into his pants pocket and fished out a memory card full of state secrets, for which he could now be hanged. He put the card in his mouth, chewed it into pieces and swallowed.

Shortly after that, agents of the Iranian Intelligence Ministry entered the room, and the interrogation began, interspersed with beatings, Hosseini says. His denials and destruction of data were useless; it seemed they already knew everything. But how?

"These are things I have never told anyone in the world about," Hosseini told Reuters. As his thoughts raced, Hosseini even wondered if the CIA itself had betrayed him.

Hosseini was the victim not of betrayal, but of CIA negligence, as revealed by a year-long Reuters investigation into the CIA's attitude towards its informants. A faulty secret communications system allowed Iranian intelligence to easily identify and capture him. While in prison for almost a decade and speaking for the first time, Hosseini said he had not heard anything from the CIA, even after his release in 2019.

The CIA declined to comment on Hosseini's version.

The experience of Hosseini's careless treatment was not unique. In interviews with six Iranian former CIA informants, Reuters found that intelligence was negligent in other cases amid an intense drive to gather intelligence in Iran, endangering those who risked their lives to help the United States.

One informant said that the CIA had instructed him to transmit information in Turkey at a place that the agency knew was under Iranian surveillance. Another man, a former government employee who traveled to Abu Dhabi for a U.S. visa, claims that a CIA officer unsuccessfully tried to push him to spy for the United States, which led to his arrest when he returned to Iran.

Such aggressive actions by the CIA sometimes endanger ordinary Iranians, who have little chance of obtaining important intelligence. According to six Iranians, when these men were caught, the agency did not provide any assistance to the informants or their families even years later.

James Olson, the former head of CIA counterintelligence, said he was not aware of these specific cases. But he said that any unnecessary compromise of sources by the agency would constitute both a professional and ethical mistake.

"If we act carelessly and recklessly, then we should be ashamed," Olson said. "If people trusted us enough to share information, and they paid for it, then we suffered a moral defeat."

These people were imprisoned as part of an aggressive purge undertaken by Iran's counterintelligence, which began in 2009. The campaign was made possible in part by a series of CIA blunders, according to news reports and three former U.S. national security officials. In state media reports, Tehran said its mole hunt eventually led to dozens of CIA informants.

Reuters conducted dozens of hours of interviews with six Iranians who were convicted by their government for espionage between 2009 and 2015.

To verify their reports, Reuters interviewed 10 former U.S. intelligence officials with knowledge of operations in Iran; reviewed Iranian government reports and news reports; and interviewed people who knew the spies.

None of the former or current U.S. officials who spoke to Reuters confirmed or disclosed the identities of any CIA sources.

The CIA declined to comment specifically on the Reuters findings or the intelligence agency's operations in Iran. The spokeswoman said the CIA is doing everything possible to protect people who work with the agency.

Iran's foreign ministry and its mission to the United Nations in New York did not respond to requests for comment.

Hosseini was the only one of the six people interviewed by Reuters who said he had been assigned a vulnerable messaging tool. But an analysis conducted by two independent cybersecurity experts showed that the now-defunct system of hidden online communication used by Hosseini, discovered by Reuters in the Internet archive, could expose at least 20 other Iranian spies and possibly hundreds of other informants working in other countries.

This messaging platform, which operated until 2013, was hidden behind rudimentary news and hobby sites where spies could go to contact the CIA. Reuters has confirmed its existence in four former U.S. officials.

Failures continue to haunt intelligence years later. Last year, in a series of internal cables, the CIA leadership warned that it had lost most of its spy network in Iran and that sloppy intelligence techniques continued to threaten the CIA's work around the world, the New York Times reported.

The CIA considers Iran one of its most difficult targets. Since Iranian students seized the American embassy in Tehran in 1979, the United States has not had a diplomatic presence in the country. Instead, CIA officers are forced to recruit potential agents outside of Iran or through online communications. The weak local presence puts American intelligence at a disadvantage against the background of events such as the current protests that have engulfed Iran in connection with the death of a woman arrested for violating the country's religious dress code.

Four former intelligence officers interviewed by Reuters said the CIA is willing to take more risks with sources when it comes to spying on Iran. Curbing the Islamic Republic's nuclear ambitions has long been a priority for Washington. Tehran insists that its nuclear efforts are aimed exclusively at energy needs.

"This is a very serious, very serious intelligence goal to penetrate Iran's nuclear weapons program. You don't have a higher priority than that," said James Lawler, a former CIA officer who dealt with weapons of mass destruction and Iran. "So when they do a risk-reward analysis, you have to take into account the incredible returns."

Much has been written about the long-standing shadow war between Iran and Washington, in which both sides avoided a full-scale military confrontation, but committed sabotage, assassinations and cyber attacks. But six informants interviewed for the first time by Reuters gave an unprecedented first-hand account of the deadly espionage game from the perspective of Iranians who served as CIA foot soldiers.

Six Iranians have served prison sentences ranging from five to ten years. Four of them, including Hosseini, remained in Iran after their release and may still be re-arrested. Two fled the country and became stateless refugees.

Six men admitted that their CIA handlers never made firm promises to help if they were caught. Nevertheless, everyone believed that US help would come one day.

The arrests of spies could call into question the credibility of the CIA as it seeks to rebuild its spy network in Iran. The country's state media covered some of these cases, portraying the agency as helpless and incompetent.

"This is a stain on the U.S. government," Hosseini told Reuters.

CIA spokeswoman Tammy Kupperman Thorpe declined to comment on Hosseini, the affairs of other captured Iranians, or any aspects of how the agency conducts operations. But she said the CIA would never be careless about the lives of those who help the agency.

"The CIA takes its obligations to protect the people who work with us very seriously, and we know that many do it bravely, putting themselves at great risk," Thorpe said. "The notion that the CIA will not work hard to protect them is false."

Evil initiatorHosseini's move to espionage came after he climbed a steep path to a lucrative career.

The son of a tailor, he grew up in Tehran and studied turning and auto mechanics, he said, showing Reuters his diploma from a vocational school.

According to him, teachers noticed Hosseini's intelligence and pushed him to study industrial engineering at the prestigious Technological University. Amir Kabir. Hosseini said a professor there introduced him to a former student connected to the Iranian government who eventually became his business partner.

Their engineering company, founded in 2001, provided services to optimize energy consumption by enterprises. At first, the firm worked mainly with food and steel mills, Hosseini said, eventually concluding contracts with the Iranian energy and defense industries. Hosseini's account of his professional experience is confirmed by corporate records, reports in the Iranian media and interviews with six partners.

Hosseini said the success of the company made his family rich, which allowed him to buy a big house, drive imported cars and go on vacation abroad. But in the years after the election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who held this position from 2005 to 2013, his business faltered.

Under Ahmadinejad, a hardliner linked to the country's theocratic ruler, representatives of Iran's security forces were encouraged to infiltrate the industrial sector, strengthening the military's control over lucrative commercial projects. According to Iranian democratic activists, reputable companies were often relegated to the role of subcontractors for these newcomers.

Soon, Hosseini said, all of his new contracts had to be routed through some of these people, which forced him to lay off workers as incomes fell.

"They didn't know how to do the job, but they took the lion's share of the profits," Hosseini said, raising his voice as he recounted the events a decade later. "It was as if you were the head of the company, did everything from 0 to 100 and saw how your salary was given to the youngest employees. I felt raped."

At the same time, the US rhetoric against Ahmadinejad was growing. Washington viewed the Iranian president as a dangerous provocateur bent on creating nuclear weapons. Hosseini began to feel that his life was being destroyed by a corrupt system and that the government was too unstable to afford nuclear weapons. His anger grew.

One day in 2007, he said he had opened a publicly accessible CIA website and clicked a link to contact the agency: "I am an engineer who worked at the Natanz nuclear site and I have information," he wrote in Persian.

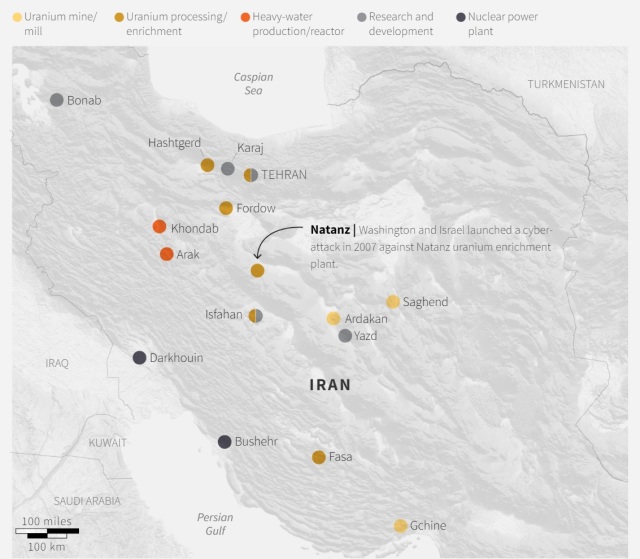

Located 200 miles south of Tehran, Natanz is a major uranium enrichment facility. The archived web records of Hosseini's engineering firm for 2007 state that the company worked on civil electric power projects. Reuters could not independently confirm Hosseini's work in Natanz.

A month later, to his surprise, Hosseini said he had received an email from the CIA.

Part of the team?Three months after this contact, Hosseini flew to Dubai.

At the fashionable Souk Madinat Jumeirah shopping market, he was looking for a blonde with a black book in her hands. He was standing outside the restaurant where they had agreed to meet when she arrived accompanied by a man.

The restaurant manager led them to a table in the corner. The woman introduced herself only as Chris, speaking in English, while her colleague translated into Persian. Sipping a glass of champagne, Chris told him that they were the ones Hosseini had been messaging with over the past few months on the Google chat platform. She asked Hosseini about his work.

According to Hosseini, he explained that a few years ago his company was working on contracts to optimize the flow of electricity at the Natanz site, a complex work that allows you to maintain the rotation speed of centrifuges at exactly the speed that is necessary for uranium enrichment. Located in the central part of Iran, Natanz was the heart of Tehran's nuclear program, which, according to the government, was supposed to produce civilian electricity. But Washington viewed Natanz as the basis of Iran's desire to acquire nuclear weapons.

Hosseini told Chris that his firm was a subcontractor of Kalaye Electric, a company that was sanctioned by the U.S. government in 2007 over its alleged role in Iran's nuclear development program. He added that he is looking for additional contracts at other important nuclear and military facilities.

Kalaye Electric did not respond to requests for comment.

The next day, the three met again, this time in Hosseini's hotel room overlooking the bay. Hosseini unfolded a maze-like diagram on the table showing the connection of electricity to the nuclear plant in Natanz. "At the same time, Chris's mouth opened wide," Hosseini recalls.

Hosseini explained that despite the fact that the scheme is already several years old, the volumes of energy entering the facility displayed on it gave Washington the basis for estimating the number of centrifuges currently operating. He believed that these data could be used to assess progress in the processing of highly enriched uranium needed for nuclear weapons.

Hosseini said he didn't know it at the time, but Natanz was already under the gun of the US authorities. In the same year, Washington and Israel launched cyber weapons that were supposed to disable these very centrifuges, infecting them with a virus that would paralyze uranium enrichment in Natanz for many years, as security analysts concluded. Reuters was unable to determine whether the information provided by Hosseini contributed to this cyber sabotage or other operations.

At subsequent meetings, Hosseini said, the CIA asked him to pay attention to a broader U.S. goal: identifying possible critical points in Iran's national electricity grid that could lead to prolonged and paralyzing power outages in the event of a missile hit or sabotage.

Hosseini said he continued to meet with the CIA in Thailand and Malaysia - a total of seven meetings in three years. To demonstrate proof of his travels, Hosseini provided photographs of the entry stamps in his passport for all trips except the first two, for which, according to him, he used an old, now discarded passport.

As the relationship progressed, Chris was replaced by a male curator. He was accompanied by officials who, according to the description, held higher positions in CIA operations in Iran, as well as technical experts who could keep up with his engineering jargon.

The new role motivated Hosseini, giving his work a sense of urgency and purposefulness. He struggled to win a case that would give him greater access to the information the CIA was looking for. He said his company had contracted with a unit of Setad - part of a sprawling business conglomerate controlled by Iran's supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei - to assess the electricity needs of a giant commercial and commercial construction project in northern Tehran.

As representing the supreme leader's commercial organization, Hosseini insisted that the state-owned energy company Tavanir supply the electricity needed for the sprawling construction. When Tavanir stated that it did not have enough electricity to meet the gigantic needs of the project, Hosseini asked the company to conduct an in-depth analysis of the national power grid. This allowed him to gain access to diagrams showing how electricity is supplied to nuclear and military facilities and how critical points of the network can be sabotaged.

Setad and Tavanir did not respond to requests for comment.

In August 2008, a year after he became a spy, Hosseini said he met with an elderly, broad-shouldered CIA officer and others at a hotel in Dubai.

"We need to expand the commitment," Hosseini told the officer. The officer handed Hosseini a piece of paper and asked him to write a promise that he would not provide the information he shared to another government - a CIA practice aimed at strengthening the sense of commitment on the part of the informant, as two former CIA employees said.

Then another CIA officer who was present at the meeting showed Hosseini a secret communication system that he could use to communicate with his handlers: a primitive football news website in Persian called Irangoals.com . Entering the password into the search bar caused a secret message pop-up window, allowing Hosseini to send information and receive instructions from the CIA.

When Hosseini complained that during one of the trips his daughter turned three, a CIA officer bought him a teddy bear to give to the child. "I felt like I joined the team," Hosseini told Reuters.

Breakdown of the secret systemWhat Hosseini didn't know was that the world's most powerful intelligence agency had provided him with a tool that probably led to his capture.

In 2018, Yahoo News reported that a compromised secret Internet communication system led to the arrest and execution of dozens of CIA informants in Iran and China.

Reuters has discovered a secret CIA communications site identified by Hosseini, Irangoals.com, at the Internet Archive, where it remains publicly available. Reuters then asked two independent cyber analysts - Bill Marczak of the University of Toronto's Citizen Lab and Zach Edwards of Victory Medium - to find out how Iran could exploit weaknesses in the CIA's own technology to expose Hosseini and other CIA informants. The two are experts in privacy and cybersecurity and have experience analyzing electronic intelligence operations. This work represents the first independent technical analysis of an intelligence failure.

Irangoals.com it looked like a website for sports fans. But what looked like a search bar was actually a password entry field - the HTML code of the search bar contains the word "password". Entering the password into the search bar started the login process. A successful login opened access to a hidden messaging interface for communication with the CIA.

Marczak and Edwards quickly discovered that a secret messaging window hidden on the site Irangoals.com, can be detected by simply right-clicking on the page to bring up the encoding of the website. This code contained descriptions of secret functions, including the words "message" and "compose"-easily detectable signs that the site had a built-in messaging capability. The code for the search bar that launched the secret messaging software was marked as "password".

Independent analysts concluded that the site Irangoals.com it was far from a specialized high-end spy product. It was one of hundreds of websites that the CIA created en masse to provide to its sources. These rudimentary sites were dedicated to topics such as beauty, fitness, and entertainment, including the Star Wars fan page and the page of the late American talk show Johnny Carson.

Each fake website was assigned to only one spy to limit the disclosure of the entire network in the event of the capture of any one agent, two former CIA officials told Reuters.

But the CIA has made it easier to identify these sites, independent analysts say. Marczak discovered more than 350 websites containing the same secret messaging system, all of which had been unavailable for at least nine years and archived. Edwards confirmed his findings and methodology. The online records they analyzed show that the hosting space for these fake websites was often purchased in bulk by dozens, often from the same Internet service providers, on the same server. As a result, the numeric IDs or IP addresses for many of these websites were consistent, like houses on the same street.

"The CIA really failed on this issue," said Marczak, a Citizen Lab researcher. According to him, the secret messaging system "stuck out like a sore thumb."

In addition, some sites bore strikingly similar names. For example, while Hosseini was communicating with the CIA via Irangoals.com, a website was created for another informant called Irangoalkicks.com . Analysts found that at least two dozen of the more than 350 sites created by the CIA turned out to be messaging platforms for Iranian operatives.

In general, these features meant that detecting one spy using one of these websites would allow Iranian intelligence to uncover additional pages used by other CIA informants. Once these sites were identified, it would be easy to detain the operatives using them: the Iranians just had to wait and see who would show up. In fact, the CIA used the same row of bushes for its informants around the world. According to analysts, any attentive spy rival would be able to detect them all.

This vulnerability has gone far beyond Iran. Analysts have found that websites written in different languages serve as a channel for the CIA to communicate with operatives in at least 20 countries, including China, Brazil, Russia, Thailand and Ghana.

CIA spokeswoman Thorpe declined to comment on the system.

Reuters has confirmed the intelligence failure on the CIA's template websites of three former national security officials.

According to former US officials, the CIA was not aware that this system was compromised until 2013, after many of its agents began to disappear.

However, the CIA has never considered the network secure enough for its most valuable sources. According to three former CIA officers, high-ranking informants receive custom-made covert communication tools created from scratch at the agency's headquarters in Langley, Virginia, so that they easily fit into the spy's life without attracting attention.

According to them, mass sites were intended for sources that were either not considered fully verified, or had limited, albeit potentially valuable, access to state secrets.

"It was given to a person who is not worth the investment for advanced intelligence tools," said one former CIA employee.

The CIA declined to comment on the secret communications system and the intelligence failure.