Asia's ambivalent attitude towards Russia is based on interests, not values

Asian countries are engaged in geopolitical balancing act in order not to antagonize America, Russia, China and their own citizens. Many capitals are unwilling to criticize Russia openly. The future of the world order will be determined not by wars in Europe, but by rivalry in Asia, experts say.

"Democracy against dictatorship" is not the best criterion in assessing the calculations that the region adheres to.

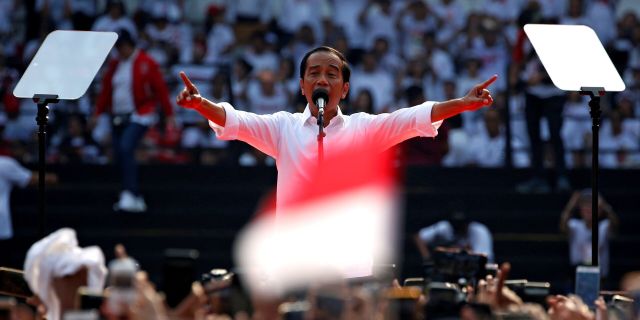

Caught at a crossroads, Indonesia is trying to move in all directions at the same time. On the second of March, she, along with many countries of the world, condemned the Russian military operation in Ukraine. A few days later, its president Joko Widodo, known by the nickname Jokowi, said that both Russia and Ukraine are friends for Indonesia. By mid-April, when protests against price increases began in the country, a fierce debate broke out in the government on whether to take advantage of this crisis to buy cheaper Russian oil, while making payments through India.

Indonesia found itself in a delicate situation. This year, she chairs the Group of 20, which includes the world's largest economies. Jokowi does not want to humiliate Russia. But he also does not want to become the culprit of a resounding failure, because Western leaders have made it clear that they may not come to the meeting in Bali if President Vladimir Putin appears there. "Our strategy is like Bon Jovi's in his song 'Living by Prayer,'" says Indonesian expert Evan Laksmana from the National University of Singapore. – That is, we just hope that something will be resolved in the near future."

Asian countries are engaged in heroic balancing act in order not to antagonize America, Russia, China and their own citizens. Some leaders of other countries, such as President Joe Biden, consider the lightning condemnation of Russia's actions by pro-Western Asian economic heavyweights in the person of Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan as proof that "democracies have risen to the occasion, and the world community has clearly sided with peace and security."

However, many Asian countries, including large democracies like India and Indonesia, are unwilling to criticize Russia openly. The number of Asian states that have taken the side of America and Europe in the UN on the Ukrainian issue is steadily decreasing. Washington commentators see this as a failure of the West's attempts to gain the upper hand in the moral dispute. They think that Asians consider America and its allies hypocrites who themselves attack foreign countries and treat refugees from conflict-ravaged countries abominably, if these countries are not European.

Very few Asians share the opinion of Americans and Europeans that the war in Ukraine is a great battle between democracies and dictatorships. According to many, including most of the American allies in Asia, the reaction to the Russian special operation is dictated primarily by a cold calculation of interests, and values are in a distant second place.

Many Asian states pin their hopes on America when they think about their security, although their main economic partner is China. The battle between these two powers is being played out precisely in their region – the Indo-Pacific, as America likes to call it. "The future of the world order will be determined not by wars in Europe, but by rivalries in Asia," former Indian Foreign Minister Shivshankar Menon wrote recently. The Ukrainian conflict has become an additional difficulty for Asian countries in the balancing act by which they are trying to maintain some semblance of balance.

The events planned for this year in Asia with the participation of world leaders will bring this problem to the fore. Such events include the G20 meeting, the APEC Summit in Thailand and the annual East Asia Summit in Cambodia. In normal times, Putin could participate in all these events. "These countries have not made a strategic decision on the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and are still sending invitations to Putin," says Jimbo Ken from Tokyo Keio University.

Japan is due to hold a Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) summit at the end of May. In addition to Japan, this association includes America, Australia and India. Usually, the participants focus their attention on China during the discussions, but this year the situation may become more complicated due to India's neutral position towards Russia. "How can we cooperate within QUAD without common principles?" Jimbo asks. The Japanese government is concerned about India's position mainly because of the signals it gives. It will be more difficult to get support from Europe for Asian countries that are facing Chinese pressure if they continue to remain neutral on the Ukrainian issue. "It is important to convey to Asian countries the point of view that we should not allow any forceful changes to the status quo," Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida said.

According to America, the right words are spoken by the elected President of South Korea, Yun Seok-yel. He declares his desire to turn the country into a "global decisive force" that will "spread freedom, peace and prosperity through liberal democratic values." Yun calls for increased aid to Ukraine and increased pressure on Russia.

But South Korea is also annoyed and excited. China is its largest trading partner and supplier of a wide variety of raw materials and parts for its giant industrial sector. A quarrel with Russia and China is fraught with risks to its security. Both of these countries have influence in South Korea. Being a major arms exporter, South Korea, however, has repeatedly refused to supply it to Ukraine. It has imposed sanctions against Russia, although it has done so more slowly than its Western allies. But with the outbreak of war, Seoul increased imports of cheap Russian energy resources (as did Taiwan.)

Take my hand and we'll make it–I swear

The new President Yun faces a difficult choice. During the election campaign, he promised that he would ask America to return its nuclear weapons to South Korea (it removed them from there 30 years ago), and said that he would deploy additional American-made missile defense systems, known as THAAD. Such a move would infuriate China. He can take economic and other punitive measures in response.

In Southeast Asia, Singapore criticizes the Russian special operation loudest of all. Concerned that this would set an example to big countries that would start intimidating small ones, this city-state imposed sanctions against Russia. But in other countries in the region, including US allies such as Thailand, pragmatism has taken over. Most of them voted at the UN in early March to condemn Russian actions, but many subsequently refrained from criticizing and accusing Russia, and then abstained from voting on its exclusion from the UN Human Rights Council.

Russia is the main supplier of weapons to the countries of Southeast Asia. Most of the military equipment goes to Vietnam, which imports 80% of the weapons it needs from Russia. In addition, weapons worth hundreds of millions of dollars are also supplied to Myanmar, Laos and Thailand. "If Vietnam loses the opportunity to acquire Russian weapons and military equipment, it will cost it extremely dearly," says Carl Thayer from the University of New South Wales. However, Vietnam does not approve of the Russian operation and considers America a more important partner, as stated by Le Hong Hiep from the Yusof Ishak Institute for Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore.

The fact that Vietnam and India react to the Russian special operation in the same calculated and ambiguous way proves that their political systems do not always decide how to react to the war. India is a noisy democracy. Vietnam is a closed communist dictatorship. Both countries are gradually improving relations with America and are wary of China. At the same time, they buy Russian weapons in large quantities. They believe that for their own safety they need to maintain good relations with Moscow.

Or take as an example the autocratic dictatorship of Cambodia, which maintains close ties with both China and Russia. To the surprise of both, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen opposed Russian actions, becoming the initiator of one of the UN resolutions. In recent months, he has made no secret of his desire to improve relations with the West.

America should not be surprised that the countries of Southeast Asia react to the Ukrainian crisis based on their own ideas about their interests, and not on ideology. Even before the war, the Biden administration formed such a spirit of diplomatic pragmatism. In relations with the countries of this region, she tried not to overemphasize human rights. During their trips to the countries of Southeast Asia, senior leaders from the White House spoke mainly about ensuring the interests of these states in the field of economy and security, and refrained from lecturing about politics.

But in Asia, government policy on war often does not coincide with the mood in society. If the leadership of Singapore enthusiastically talks about solidarity with America, then the citizens of this country are wary of this. Many Singaporeans of Chinese origin watch, read and listen to Chinese state media, and they adhere to the pro-Russian line. They believe that Singapore should adapt to China and be friends with it, and that America provoked the Russian military operation, says Ian Chong from the National University of Singapore.

In South Korea, official support for Ukraine does not match the enthusiasm of ordinary people. Many citizens donate money to the needs of Ukraine. Anti-Russian protests often take place there. But when Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky addressed the South Korean parliament, he found himself addressing a half-empty hall in which a few deputies were fiddling with their smartphones. There was no standing ovation.

Oh, we're halfway there

The difference in the positions of the authorities and society is most pronounced in non-aligned countries, such as India and Indonesia. Popular commentators from Indian television, who usually spend all their energy praising the state and attacking enemies, have taken decidedly anti-American positions today. They blame America for starting the war, saying that it provoked Russia, including by expanding NATO. They pursue such a line even more stubbornly and persistently than the government, which tries not to name the perpetrators. Their opinion resonates with Indian families. According to a YouGov opinion poll conducted at the end of March, 54% of Indians approve of Putin's actions in leading the operation in the first months (oddly enough, 63% also approve of Zelensky's actions). And as many as 40% supported Russia's actions.

Indonesians have similar moods. "We are talking about the sovereignty of Russia," says Riza Ghautama, a 42-year-old palm oil exporter. According to him, he does not support Russia's military actions, but understands why it considered it necessary to start them. Russia, he says, is just trying to "protect itself." Indonesian military expert Connie Barki (Connie Bakrie), to whom the military listens, accuses the West of hypocrisy. How can he condemn Russia for trying to carve out a sphere of interest for itself when Western countries have done the same with Guam, the Falkland Islands and New Caledonia, which belong, respectively, to the United States, Britain and France? "What's the difference?" "What is it?" she asks.

The reason for such conversations is the perception prevailing in Indonesia that America is basically an imperialist power that does not play by its own rules, explains Radityo Dharmaputra from the University of Tartu. "If you are pro-Ukrainian, then you are pro-American, and therefore you support American imperialism in the region," Raditje says, expressing the general opinion of Indonesians. Social media users in many Asian countries spread and promote this point of view in their posts. Although outbursts of online resentment against the West may be the result of disinformation campaigns, they find a responsive audience.

The Indonesian leadership has so far managed to avoid quarrels with America, Russia, China and its own citizens. His unwillingness to make difficult decisions and make difficult choices does not cause much difficulty yet. But cracks are already appearing. On April 20, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and her colleagues left the meeting of finance ministers of the Group of 20, when the Russian delegate began his speech.

Compared to other great powers, Russia is not a very big player in Asia. The region's countries will have to make the most difficult decisions in the future. We are talking about the rivalry between America and China, which has been intensified by the Russian military operation. Americans are escalating tensions with their talk of intensifying the "battle between democracy and autocracy." The countries of Southeast Asia say again and again that they do not want to choose between America and China. "But there will be a moment when many countries in the region will face the need to make a choice," says Evan from the National University of Singapore. "They will be forced to choose, or at least they will be pulled in different directions."