It is difficult to surprise with the developments of space technology today. Nevertheless, there are innovations for orbital flights that stand out for their unusual design. Can an air jet engine operate in orbit? Moreover, it can work indefinitely, and even without requiring fuel. Of course not, you might say. Nevertheless, it is possible. We will tell you more about the most unusual engines for the most promising space orbits.

Orbits at the edge of space

Near-Earth orbits are infinitely diverse in the shape of their ellipse, size and location in space. The range of their heights is also huge. Automatic observatories rise in high elliptical orbits 150 thousand kilometers above the Earth and above. Other elliptical orbits such as Molniya and Tundra for television broadcasting and missile launch detection satellites reach an apogee of 40,000 kilometers, slightly higher than the geostationary orbit with its height of 35,786 kilometers. GPS, GLONASS and other global positioning system satellites travel through space at average altitudes of approximately 19-20 thousand kilometers.

These include all kinds of civilian and military communications, remote sensing of our planet, photo services and optical reconnaissance in numerous sun-synchronous orbits, observation of dim hypersonic targets in the atmosphere, and many other applications. Manned spacecraft, the ISS and Tiangong stations fly in low orbits. Launches of their future counterparts are also planned there.

At the bottom of all this diversity lies the most unusual layer of orbits. Flying there is unique in its own way, and qualitatively different from moving in any other orbits. It provides important advantages that are not found anywhere else in space. But in order to explore these tempting orbits, it is necessary to solve unusual tasks for space satellites.

The oddities begin with the fact that the boundaries of this particular range of heights are not precisely defined. Man has designated a circular 100 kilometers (called the Pocket line, although it is actually a surface) as the formal boundary of the atmosphere and space for his convenience. In reality, the atmosphere rises much higher and can be traced up to a couple thousand kilometers. For example, the ISS, at an altitude of 415 kilometers, experiences atmospheric braking from 100 to 400 grams of force, depending on the flight altitude, the current state of the atmosphere and the position of the solar panels.

Lower air density and its braking force are increasing. At altitudes of 120-150 kilometers, the orbits lose stability: the spacecraft begins its last turn there, which is no longer complete and leads to a fall into a dense atmosphere. The transition to the final turn is also influenced by the shape of the device, its "swinging" or, conversely, streamlined compactness.

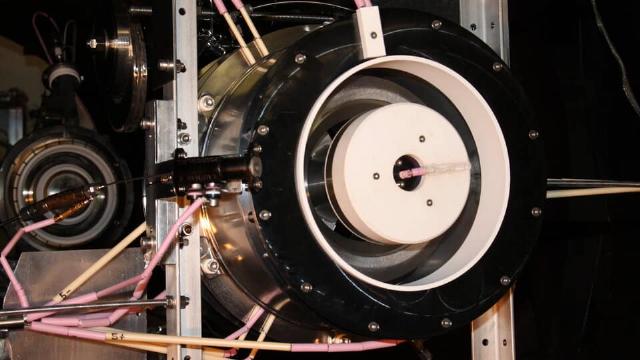

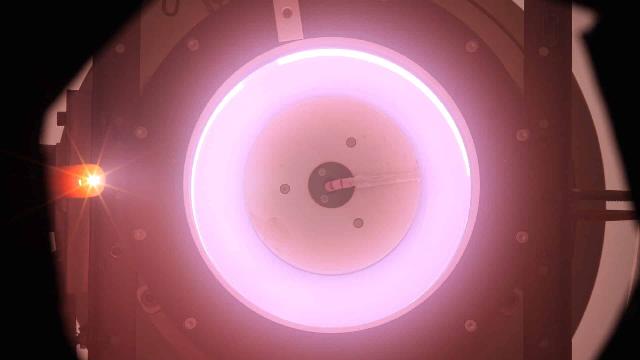

An air-ramjet engine for ultra-low orbits by the Italian company Sitael, placed in a vacuum chamber for testing. Photo: esa.int .

Such orbits have long been used in space exploration, but they do not make a complete revolution around the Earth. A rocket usually carries a payload there that has not yet separated from the last stage or upper stage. In a low orbit, the cargo with the stage "reaches" the desired area of the Earth, for example, to the pole or to another hemisphere, where the engines of the stage or upper stage are turned on.

The cargo leaves this low orbit for another one, rising higher and continuing its flight to the target orbit, where it is heading. Such temporary orbits, from which the cargo soon departs for further flight, are called reference orbits. In Russia, their usual height is around 200 kilometers, in the USA it is often 185 kilometers — around 100 nautical miles.

At altitudes of 200-250 kilometers, the satellite can be in free motion for about a week. During this time, the atmosphere will slow it down and drag it down to the heights of orbital instability, from where it will quickly dump it into a funeral pyre in dense layers.

The orbits occupying this lower edge of space are called VLEO, or Very Low Earth Orbit ("very low Earth orbits") in English-language sources. We'll make it shorter: ultra-low orbits. And they differ from all other near-Earth orbits in special properties.

The lowest are the closest

First of all, the smallest height: it gives two important advantages. The first is the proximity to ground—based surveillance facilities. Both optical and radar surveillance will provide the highest resolution and sensitivity here, which means the detail of both the optical image in any range and the radar image. From such low altitudes, one can see dim targets below, already indistinguishable from heights of thousands of kilometers. These can be very serious and important targets: for example, relatively poorly heated hypersonic cruise missiles. And for high radar resolution at these altitudes, low power will be required from both the radiator and power supplies, simplifying the design and reducing its weight.

It should be noted that gravimetric works that measure the distribution of anomalies in the Earth's gravitational field and identify details of geological objects (for example, mineral deposits) will also have high resolution and detail from this height. It's easier to study objects on Earth and in the atmosphere, and fields near it.

The second advantage of low altitude is the minimal delay of the signal from and to the satellite. It can be extremely important for communication systems, especially for telephone calls via satellites.

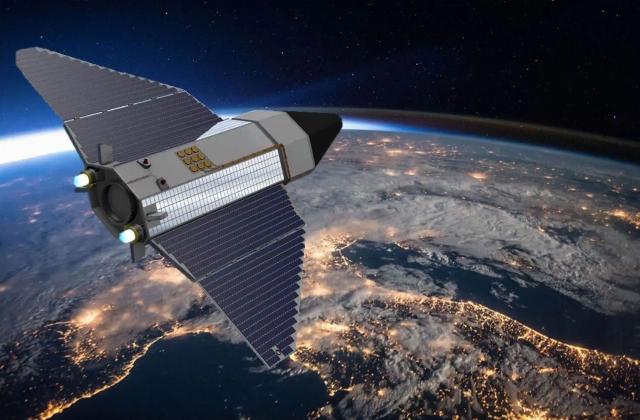

The EOI Space company from the USA plans to create a constellation of ultra-high-resolution Stingray satellites for ultra-low orbits. Source: EOI.com

The third advantage of ultra—low orbits is the absence of space debris there. There is no need to maneuver to avoid a collision and monitor the ballistic situation. The atmosphere continuously and effectively cleans these heights, quickly converting all space debris into a rare oblique rain of fire.

If a long-term, multi-year flight at this altitude were made, such an orbital system would far surpass most existing satellite groupings in terms of efficiency and capabilities.

The orbit's struggle with the atmosphere

But significant advantages, however, are accompanied by two important disadvantages generated by the same atmosphere. This is the aerodynamic drag and erosive effect on the surface of the satellite structure. The key is atmospheric braking, which counteracts prolonged flight.

It consists here of nitrogen and even more of oxygen, but not of the oxygen molecules that we breathe. Absorbing the energy of solar ultraviolet radiation, O2 molecules break down into individual atoms here. And this atomic oxygen is heated to a temperature of 1000 ° C or more, which is why this part of the atmosphere is called the thermosphere.

However, such a rarefied environment cannot significantly warm up the structure. But atomic oxygen is chemically very active, and acts on the surface of the satellite by oxidation, corroding materials and changing their properties. And most importantly, the continuous flow of oxygen atoms hitting the flying structure at tremendous orbital speed inexorably slows down the satellite, lowering its altitude and plunging it into the zone of orbital instability and the beginning of its last fiery revolution.

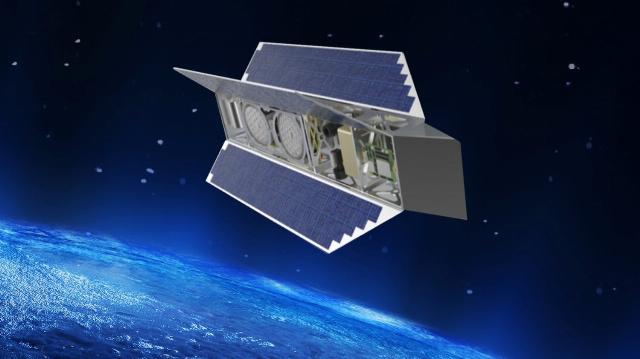

An image of a satellite for VLEO with a ramjet engine developed by the ATLAS Research and Development Center at the University of Stuttgart in Germany. Source: CRC ATLAS

It was atmospheric braking in an ultra-low orbit that determined the historic launch of the first cosmonaut. The target orbit of the Vostok-1 spacecraft with Gagarin on board had a perigee at an altitude of 181 and an apogee at an altitude of 235 kilometers. In the event of a failure of the ship's braking propulsion system, the atmosphere would have completed the orbital flight in four days, for which an on-board supply of food, water and oxygen was provided with a reserve.

However, the delay in executing the radio command to turn off the third-stage engine extended thrust and increased momentum, raising the apogee of the spacecraft's orbit to 327 kilometers. A free exit from it would take, according to various estimates, 20-50 days. Fortunately, the flight of the first cosmonaut ended safely (engine braking worked), and atmospheric deceleration was not necessary for de-orbiting. But for long-term operation in an ultra-low orbit, this deceleration is a critical problem.

Possible solutions to the braking problem

It can be solved in two directions at once. The first is to reduce the drag of the structure. To do this, the satellite body must be elongated and narrow: the smaller the satellite's cross-sectional area, the less braking. For the same reasons, the solar panels should be stretched along the body, like the tail of an arrow.: this way they will create the least resistance.

It would be nice to sharpen the front part of the satellite, making it wedge-shaped. And also use special smooth mirror-type materials there, upon impact with which oncoming oxygen atoms will obliquely bounce off them, reducing the braking impulse transmitted to the satellite.

These measures will reduce, but not eliminate, air resistance. Its remainder can be compensated by the thrust of the engine, and this is the second direction of combating atmospheric braking. For a long flight, the engine needs to run for an equally long time. Chemical engines are no good: they will burn the fuel too fast, it will not be enough for many months or years of flight.

First, the engine detaches an electron from the neutral atom of these gases; the resulting charged ions are responsive to the accelerating effect of the electric field of the engine. They are accelerated by the field and fly out of the nozzle at great speed, creating a reactive force. The supply of several kilograms of krypton is enough for several months of engine operation.

European gravimetric satellite GOCE for long-term operation in ultra-low orbit ESA

Image Source: AOES Medialab

This was the European gravimetric satellite GOCE (Gravity Field and Steady-State Ocean Circulation Explorer — "researcher of the gravitational field and steady ocean currents"), made for long-term operation in an ultra-low orbit. Launched by a Russian rocket from Plesetsk in March 2009, it operated for four years in a circular orbit 255 kilometers high. This was achieved thanks to the elongated aerodynamic shape of the five-meter hull and the solar panels stretched along the hull, which strongly resemble the tail of an arrow. As well as the continuous operation of two electric jet engines and an on-board xenon reserve of 40 kilograms. After running out of xenon, the satellite lost thrust, slowed down, and burned up in the atmosphere in November 2013.

Space Pegasus on the footboard

What if we use not only the xenon that has been lifted into orbit, but also the oxygen atoms and ions already there? The electric field of the engine will accelerate them to high emission rates. The atomic mass of oxygen is five to eight times less than that of krypton and xenon; at the same rate of departure from the engine, the reactive force from the release of an oxygen ion will be just as weak. But it will be there: the engine will create thrust. This idea is one step away from the key idea: oxygen atoms can be collected from the surrounding space — more precisely, from the oncoming stream.

At this speed, the oncoming oxygen atom will hit the device, transferring its braking impulse to it — the product of the atom's mass and its speed. To accelerate the device reactively, it is necessary to eject an oxygen ion (its mass is almost equal to the mass of an atom) much faster. Then the device will receive from the ion a reactive impulse much greater than the braking impulse from the oncoming impact. For example, the engines of the GOCE satellite, which we already know, emitted xenon ions at a speed of more than 40 kilometers per second, five times faster than flight in an ultra-low orbit.

The project of an ultra-low-orbit satellite with an ABEP ramjet propulsion system by the Barcelona startup Kreios Space. Source: kreiosspace.com

The project of an ultra-low-orbit satellite with a ramjet propulsion system ABEP by the Barcelona startup Kreios Space

Some of the impacts of the oncoming atoms will simply have to affect the design of the device and will not enter the engine. Their braking effect must be compensated by the reactive thrust from the ions passing through the engine. This way, the aerodynamic drag can be completely balanced, and the device will fly without loss of speed and decrease.

There are only scanty remnants of air in the deep cosmic vacuum. But the huge flight speed allows the air intake of the device to capture a large volume in a second, and in this large volume there will be enough oxygen atoms for the engine. The main thing is that the atmosphere is inexhaustible. Its atoms will never run out, and the thrust of the engine will never run out.

Especially if the electricity for ion dispersal is taken from the sun's rays using batteries. It is only necessary to provide a reserve of electricity in the batteries for the shadow part of the orbit, which, by the way, is always shorter than the illuminated part. This will result in a "perpetual motion machine", the operation of which is not limited by the reserve of the working fluid or energy: both are inexhaustibly taken from the environment. The operating time of the engine will be limited only by the physical wear of its systems and elements, and a gradual decrease in their performance characteristics.

What's in my name for you

There is no stable generally accepted name for such an engine yet. It is airy, since it works in the opposite air. It is electrosetting, since it creates a reactive force by electric acceleration of ions. Air in the form of oxygen atoms enters the air intake, is ionized and accelerated out of the nozzle. In English-language literature, they often write "Air—breathing ion engine (ABIE)" - "air ion engine". Or RAM-EP / RAM-electric propulsion "ramjet engine", Air-breathing electric propulsion (AEP) "air-electric motor".

In Russian works, there are "ion air-jet engine (IVRD)" and "direct-flow electric jet engine (PERD)". For simplicity, we will call such an engine an aerospace engine.

The issue with straightness is: it implies only a translational, "direct" flow of air in the flow part, without rotating it with compressor blades. Only the oncoming high-speed head does all the compression work in the engine. The choice of a specific technical engine design will determine whether it will become direct-flow.

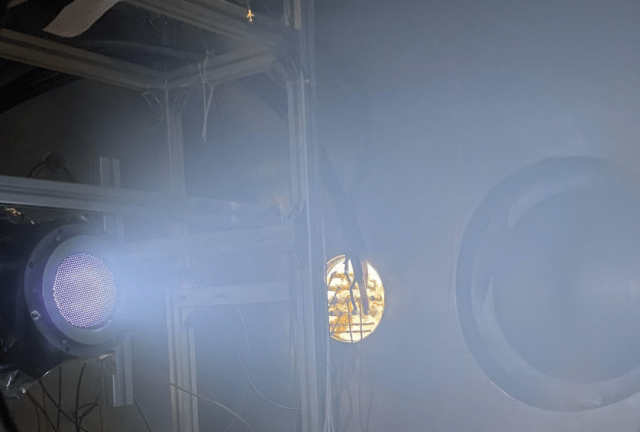

Experimental ramjet space ion engine of the Japanese space agency JAXA Photo: JAXA.

Such a direct-flow scheme is also possible: oxygen atoms entering the air intake are reflected by the narrowing surfaces of the structure inward, concentrating in a narrow neck. Then, with a powerful electric arc, the atoms are heated to ionization and enter the accelerating electric field of the nozzle part. To effectively reflect and "bounce" atoms off the air intake surfaces, special oxygen-resistant materials will be required to prevent atoms from "sticking" in them. You may need small angles of inclination of these surfaces and other technical tricks for the efficiency of the workflow.

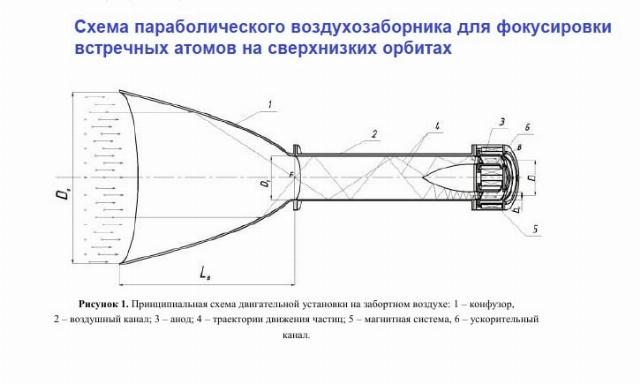

For example, the air intake can be shaped like a single-cavity paraboloid facing the bell towards the flow. Atoms flying almost parallel and in a straight line will be reflected from the walls of the paraboloid into its focus, like parallel rays of light. But not strictly to the point, but because of its speed variation and atomic motion, it is smeared into a tight area around the geometric focus point. However, this is enough to solve the problem of primary compression. This way, oxygen atoms will focus in a tight area (focusing is an unusual thing for gas dynamics!). There, an air duct will begin, in the profiled narrowing of which oxygen will slow down to an acceptable supersonic level, compacting for subsequent ionization.

Diagram: Ryazanov V. A., Shilov S. O. Bauman Moscow State Technical University, Moscow.

In general, it is possible to organize a non-strictly direct-flow process. And somehow set the operation of oxygen atom traps and their transportation to the ionization zone. Technical solutions and details of physical circuits and processes can be invented in different ways. The design bureaus that create such engines do not always disclose the details of their technologies.

The wave of space lowland exploration

Today, there are many developments of specialized satellites for ultra-low orbits. The American Skeyeon is making a Near Earth Orbiter satellite, similar to a chisel with a wedge-shaped nose and an arrow tail made of narrow solar panels. They want to create an orbital network at an altitude of 250 kilometers. EOI Space, a company from the US state of Colorado, is planning a constellation of ultra-high-resolution imaging satellites for the government and Stingray commerce, similar to a children's paper airplane with "wings" of solar panels. Albedo, a startup from Denver, wants to deploy an orbital network of 24 devices for ultra-sharp images from ultra-low orbit. The Chinese aerospace giant CASIC is planning a network of 192 by 2027 and 300 by 2030 for altitudes of 150-300 kilometers.

The project of the satellite for ultra-low orbits Near Earth Orbiter by the American startup Skeyeon Изображение:.esa.int .

At the same time, aerospace engines are being developed. Theoretical papers with justifications and calculations were published 10 years ago, including by Russian scientists from the Bauman Moscow State Technical University and MAI. Later, experimental designs appeared.

In 2017, the European Space Agency tested the ESA RAM-EP / Air-Breathing Hall Thruster (ABEP) ramjet engine in a vacuum chamber, demonstrating operation in conditions simulating 200 kilometers with an air intake from the Polish company QuinteScience. Its two-stage ion ionization and acceleration module was created by the Italian company Sitael. A similar project was developed by the startup Kreios Space, based in Barcelona, Spain.

Tests of the ramjet engine for ultra-low orbits by the Italian company Sitael Photo: esa.int .

The Institute of Space Systems at the University of Stuttgart in Germany has established the ATLAS Center for Joint Research on the Development of Satellite Technologies at Ultra-low Altitudes. He is developing an air intake and a plasma engine, first launched in March 2020. The air intake and engine are being developed as part of the DISCOVERER EU H2020 project.

In 2022, engineers from the Russian company Equipo presented their own version of the engine, having conducted preliminary tests with stable operation. The engine is also being developed at the Russian MAI together with colleagues from Moscow State University.

And not only by automated spacecraft. A manned long-term station in an ultra-low orbit with a height of 150-180 kilometers will provide a number of advantages compared to the ISS. Its orbit will not need to be periodically raised, as there will be no descent. You won't have to dodge space debris either due to its absence. The detail of Earth observation will be much higher.

Logistics will become much more efficient: launching cargo and crews to an altitude of 150 km is cheaper and easier than 415 kilometers to the ISS. Or, from another perspective, the same rocket will deliver much more payload to an altitude of 150 kilometers than to 415 kilometers. And for waste disposal, you don't need a cargo ship with a braking propulsion system and controlled flight to the flooding point. The waste will simply be sent overboard in small portions, and after a few hours it will turn into a light celestial illumination.

The appearance of such stations will be very different from today's ones. The streamlined body, elongated along the movement, will gape with a nasal air intake. Blue ribbons of oxygen ion streams will stretch out behind the station. Or will the aerospace engines and their groups hang on consoles on the sides of the station, resembling the suspension of aircraft turbojet engines? This is still a fantasy area, but aerospace engines will make it a reality. Time will tell what it will turn out to be.

Nikolai Tsygikalo