Civil and military orbital stations

The world's first orbital station, a spacecraft with a large habitable volume designed for long—term stay of astronauts on board, was launched into space by the Soviet Union in April 1971, marking the beginning of the Salyut series of stations. Salyut-1 lived in orbit for six months and managed to host one expedition. Salyut-6 has already been visited by 16 expeditions and 27 cosmonauts in five years. The Salyut-7 station, known for its dramatic rescue story after an on-board accident, has become the last to consist of a single module (a single design launched into orbit by a single launch vehicle).

The first—generation Salyuts were created on the basis of military manned Almaz orbital stations, space outposts for surveillance and reconnaissance in the interests of the Ministry of Defense. After launching into orbit, the Diamonds received a number in the Salyutov series. The military became "Salyut-2", "Salyut-3" and "Salyut-5". The stations were equipped with various photographic equipment. The "main caliber" was the giant Agat-1 space camera, which was essentially a telescope looking at the Earth. According to the Moscow Museum of Cosmonautics, the camera had a height of 4 m, a mass of 1.5 tons, a main mirror with a diameter of 900 m, and a variable focal length of up to 7.2 m. Agat-1 used a film 800 mm wide, and details up to 35 cm could be seen in its images. The film was developed directly on board and then delivered to Earth, but the most important frames were scanned and transmitted "down" on the radio channel — and this in the 1970s! A rapid-firing cannon was installed on one of the "Diamonds", intended for self-defense of the station. As an experiment, the weapon even fired a short burst in space.

Subsequent stations of the Almaz series were already created automatically, not requiring the presence of astronauts on board, but with the possibility of receiving specialists for repair and preventive maintenance.

The next space laboratory after Salyut-7 was the world's first multimodule Mir space station, whose assembly in orbit began on February 20, 1986 with the launch of the base unit. Over the next 10 years, Mir grew with successive modules launched into space, the total mass of the station reached 140 tons. During the 15 years of its existence, 104 cosmonauts and astronauts, including 62 foreigners, visited the Soviet and Russian space "apartment building". 31 Soyuz manned spacecraft, 64 Progress cargo ships, as well as 10 American reusable Space Shuttle spacecraft arrived at the multi-module station.

The failed Mir-2

It was assumed that the Mir orbital complex would work in orbit for five years, and the next one would replace it. An article in the Cosmonautics News magazine No. 9 for 2000 says that in the 1980s, Soviet designers were working on various options for a new station. The maximum program provided for the deployment of an Orbital Assembly and Maintenance Workshop (OSEC) for the assembly and maintenance of large structures and spacecraft in orbit. As a first step, it was supposed to put the Mir-2 station into orbit and gradually add elements to it.

In 2022, the website of the Russian State Archive of Scientific and Technical Documentation reported on another declassified document on the Mir-2 project. In the assignment for the preliminary design of the new station from 1990, it is noted that its mass at the first stage would have been up to 200 tons. Mir-2 was supposed to be used for permanent pilot production of semiconductors, medicines and biological products with unique properties (and their delivery to Earth), fundamental and applied scientific research, solutions for defense tasks, as well as the implementation of international projects on a commercial basis.

Then, according to a magazine publication, in the 1990s the project seriously "lost weight": it was planned to assemble it from smaller modules, and the mass of the completed station would be less than that of the Mir in orbit.

"This project was abandoned due to lack of funds," cosmonautics historian Alexander Zheleznyakov told TASS. — In the early 1990s, the Russian space industry was experiencing certain financial difficulties, a number of programs had to be closed, and some were abandoned, but since the project to create the International Space Station appeared (many countries are involved in it), of course, the groundwork that existed at that time was used to to apply [it] to the International Space Station. Our contribution was the Zarya modules and the Zvezda service module, which we are celebrating the 25th anniversary of its launch."

The finest hour of the "Stars"

The module, which became the basis of the Russian segment of the ISS, can be considered a descendant of the Soviet combat orbital stations, since it was created on the basis of the same blocks as Almazy.

According to a publication in the journal "News of Cosmonautics", the module was developed as a stand-in for a similar component of the Mir space station in case of an emergency launch of the main one. However, in February 1986, the base unit of the world's first multimodule station successfully entered orbit. Then the module was going to be used in the construction of the Mir-2 station. After the United States and Russia agreed in 1993 to jointly create an international space station, the Mira stand-in was used in a new project.

"The International Space Station project absorbed the developments that we had on Mir-2, and some of the Americans' developments on their Freedom station, which they created, but also turned out to be in favor of the ISS," Zheleznyakov recalled. — This cooperation of various countries in the creation of a large space object has proved to be very beneficial. It helped countries both save financial resources and use the technical solutions that already existed in different countries at that time. This combination proved to be very effective."

A unique module

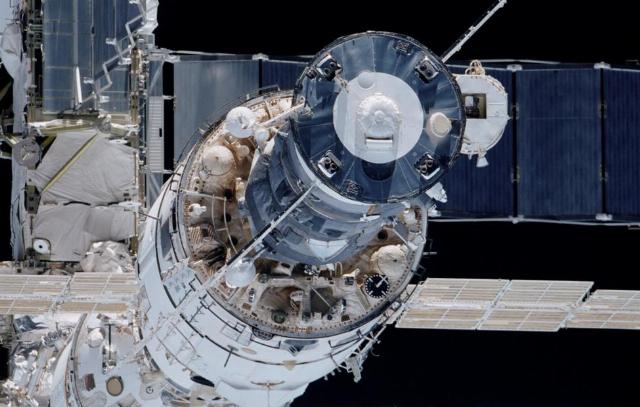

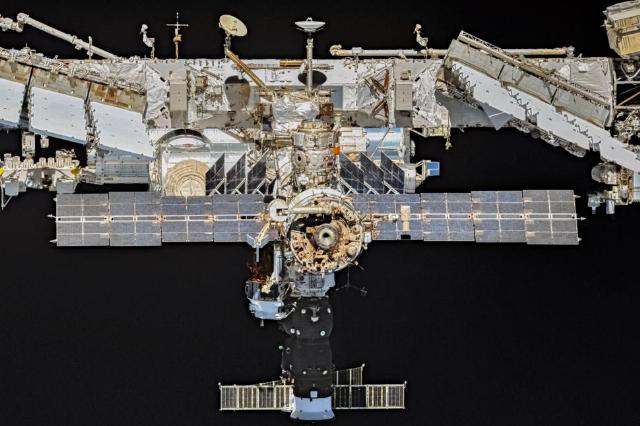

The Russian service module of the ISS, dubbed Zvezda, is one of the largest and most complex in the station. Its body length exceeds 13 m, its maximum diameter is 4.35 m, and its weight is more than 20 tons. The design allows the "Star" to exist as an autonomous habitable space laboratory. He has his own "power plant" — solar panels with a span of almost 30 m. The module is equipped with a propulsion system, with which it has repeatedly lifted the orbit of the entire ISS, with two main engines and 32 orientation engines.

© Roscosmos/ NASA

Image source: © Roscosmos/ NASA

The Zvezda transition compartment serves both to move crew members around the ISS and as an airlock during spacewalks. An independent system maintains the required temperature in the module, and the life support system ensures that up to six crew members stay on board. Zvezda has two individual cabins with portholes for astronauts and a toilet.

"If we talk about the ISS design, then Zvezda is really unique, because no other module can perform these functions," said Alexander Zheleznyakov. — Using propulsion systems on other modules, it is impossible to adjust the station's orbit. Many control systems in a single copy are installed on the Zvezda.

The future belongs to cooperation

In September 2020, a leak of the station's atmosphere was detected in the Zvezda module of the Russian segment of the ISS. It later became clear that the cause was a crack in the housing of the intermediate chamber of the module. The astronauts eliminated the leak, but experts remind us that the station's modules have reached their end of life .

"The station is really getting old, and if you take the same Zvezda module, then its warranty period was 15 years, which has already expired," Zheleznyakov recalled in an interview with TASS. — The fact that the station is aging and requires constant attention is also a fact. <...> Nevertheless, despite the detected leaks and the fatigue of the metal structure, research shows that this module and the station itself can still be operated for some time. Therefore, the agreement on work on the ISS until 2030, which currently exists, is logically justified and the station may still fly for some time."

The cosmonautics historian believes that it is worth considering de-orbiting the station when the number of failures exceeds the ability to eliminate them. "While it's flying, let's fly it," he said. — After all, this is the only opportunity to support manned space exploration both here and in the United States. Maybe India will join with its new ship."

Zvezda Service Module

Image source: © NASA/ Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Zheleznyakov recalled that when discussions began on completing the ISS mission in orbit, projects for a new joint space laboratory appeared. "At first it was a project of a circumlunar station, there were also proposals to create a station at the libration point (the point between the Earth and the Moon, in which the station, under the influence of their gravity, would be stationary relative to the planet and its natural satellite — approx. TASS)," he said. — Indeed, <...> based on the experience of working together, it all turned out very well and it would be logical to continue. If it weren't for some of the events that are taking place on Earth, if full—scale cooperation in space continued, then most likely the same cooperation — maybe even expanded - could be thinking about creating a new station on the same Moon. This is probably the simplest and most attractive option."

Victor Bodrov