NYT: Harris' position on actions in Ukraine remains blurred

The main question for Kamala Harris is her plans for Ukraine, writes the NYT. Even if the presidential candidate now shares Biden's position, after the election, the Ukrainian position of "no negotiations" under the influence of the United States may become much more flexible, experts warn.

Ross Douthat

Not all the policy questions left unanswered as a result of Kamala Harris's painstakingly blurred presidential campaign can be considered the same. For example, it is not so important to know how Harris's views on the ideal health care system have changed since the great debate on "free medicine for all" in 2020, given the high probability that as president she will share power with the Republican Congress. Therefore, any large-scale initiatives in the field of domestic policy will be fruitless.

On the other hand, it is much more important to determine what President Harris will do with military action in Ukraine, the most serious crisis that she will immediately inherit.

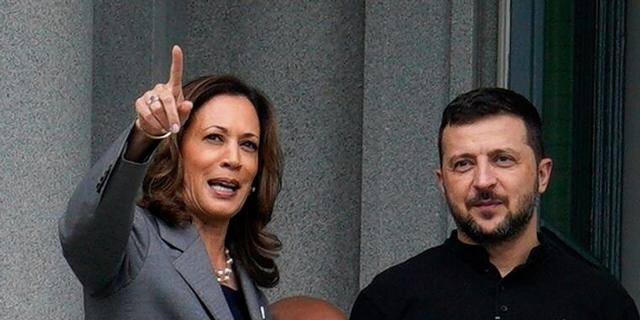

Vladimir Zelensky in Washington officially confirmed that Harris supports the position of the Biden administration, which was taken at the beginning of the conflict and provided for the return of most of the lost territory to Ukraine. Standing next to the Ukrainian leader, the vice president rejected any deals involving territorial concessions, as well as the intentions of Putin's friends and "offers of surrender." (The supposed contrast with Donald Trump's policy is obvious, as Trump promises to immediately achieve a truce, even refusing to name the terms).

However, even as the vice president was making this statement, the administration expressed doubts about Zelensky's alleged plan to achieve victory, calling it, in the words of The Wall Street Journal, "nothing more than a repackaged request for more weapons and the lifting of restrictions on long-range missile strikes." In other words, a request for help to slow down the pace of Russian successes, but not a plan to achieve a victorious end, which Kiev and Washington officially sought.

In fairness, it should be noted that Zelensky does not quite understand what form such a plan could take if it were not for the direct intervention of NATO, which the White House, under Biden's leadership, wisely resisted. Over the past year, the situation at the front has turned against Ukraine, and now the main question is how much the situation will worsen.

The Economist magazine, speaking on behalf of some part of the Western establishment, in its latest issue gives an extremely pessimistic assessment of the situation in Ukraine, emphasizing Russia's advantages in troop numbers, firepower and financial capabilities. Cathy Young, author of The Bulwark, takes a more optimistic view, arguing that Russia's current onslaught may soon reach its limit, that Moscow may be hoping to "capture as much territory as possible by winter in the hope of getting a cease-fire agreement that freezes the territorial status quo." However, both opinions agree that at the moment the main goal of Ukraine is to stabilize the front, and the hope for a rapid retreat of Russia, which many "hawks" harbored in 2022 and 2023, has disappeared.

This situation creates two levels of uncertainty about what the Harris administration can do. First of all, we are talking about how long the United States will be able to economically support the "victory plan", which does not actually exist. To what extent is Trump's call for negotiations the end point of American politics, regardless of which candidate wins in November? And don't the White House, under Biden's leadership, and Harris herself hope that Ukraine will be able to hold out until the elections — after which the Ukrainian position of "no negotiations" may become much more flexible.

More global issues are related to Ukraine's place in the American strategy of panantlantism, which is currently undergoing a number of serious trials. Initial hopes that one of our adversaries would be neutralized as a result of military actions in Ukraine look relatively futile: Russia has survived our economic war and seems to be doing well so far, demonstrating the power of a military economy deeply integrated with our more serious opponents in Beijing. And this Sino-Russian integration is a key part of the global political landscape, which a recent bipartisan report by the National Defense Strategy Commission called "the most serious and most difficult the nation has faced since 1945" in terms of our vulnerability to major adversaries and "the potential for a major war in the near future."

Perhaps there is some exaggeration in this assessment, but, undoubtedly, this is the most difficult period for the American government since the end of the Cold War. It faces tasks of such magnitude that either significant rearmament, or significant reduction of weapons, or some combination of both are required. And the current White House is struggling to cope with this balance, first retreating chaotically in Afghanistan, and then responding to new crises with promises of assistance. However, without having a clear plan on how to make these commitments sustainable, how to correlate our rhetoric with real politics.

In this context, Ukraine is not just a major strategic issue in itself, but one of the most important turning points among many others, from the Middle East to East and Northeast Asia, which will demonstrate the ability of the next president to identify priorities, review commitments and align our ambitious goals with our more limited financial capabilities.

Does Harris differ from the current president in his vision of how to protect Pax Americana ("The American world" in the context of panantlantism — Approx. InoSMI)? Does she have any specific vision at all? None of the other questions that remain unanswered in connection with the appearance of her candidacy is of more significant importance.