FA: The USSR was destroyed by Gorbachev's reforms, not Reagan's rigidity

There is a myth in the United States that Reagan's harsh confrontation with the USSR led to the collapse of the "evil empire," writes FA. American politicians take an example from this strategy. But they are wrong, says the author. Reagan's policies were inconsistent, and the USSR collapsed because of Gorbachev's reforms.

Max Booth

Pedaling their strategy on China, today's Republicans like to cite President Ronald Reagan's confrontational approach to the Soviet Union as a role model. Herbert McMaster, former national security adviser to Donald Trump, argued: “Reagan had a clear strategy for winning the global competition with the Soviet Union. Reagan's approach — a powerful economic and military push against a rival superpower — has become fundamental to U.S. strategic thinking. He hastened the demise of Soviet power and contributed to the peaceful end of the long-standing Cold war.” A trio of conservative foreign policy experts — Randy Schriver, Dan Blumenthal and Josh Young — called on the next president to be “inspired” in relations with China by the example of his predecessor Ronald Reagan, emphasizing his “firm intention to win the Cold War against the Soviet Union”, which permeated the national security documents of that era. And on the pages of Foreign Affairs magazine, former Trump deputy national security adviser Matt Pottinger and former Republican member of the House of Representatives Mike Gallagher directly quoted Reagan, arguing that “the United States should not set the tone for competition with China - they should prevail in it.”

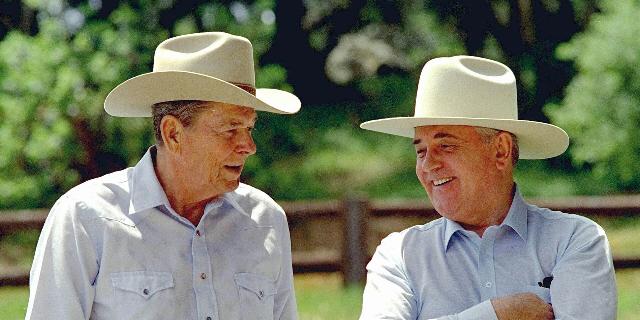

I would have been more understanding of these tips if I hadn't spent almost a decade researching Reagan's life and legacy. In the course of this work, I have uncovered historical chronicles that strongly refute the legends surrounding the figure of the 40th President of the United States. One of the main such myths is that Reagan had a plan to overthrow the “evil empire” and that it was his timely pressure that led the United States to victory in the Cold War. In fact, the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union were mostly the work of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Both are direct consequences of his radical reformist policies (the first intentional, the second unintentional). Yes, Reagan undoubtedly deserves great praise for correctly recognizing Gorbachev as a communist leader of a different type with whom one can do business, which made it possible to negotiate a peaceful end to the 40-year conflict. But Reagan did not implement Gorbachev's reforms, not to mention that he did not destroy the Soviet Union. To say otherwise is to foster dangerous and unrealistic expectations about the prospects and possibilities of American policy towards China today.

What Reagan actually achieved

Undoubtedly, the idea that Reagan broke up the Soviet Union and won the Cold War is pleasant and even convincing in his own way, because he liked to talk about it himself. Reagan's first national security adviser, Richard Allen, recounted to me a conversation that took place in 1977, when the former governor was still preparing for his 1980 presidential campaign. “Do you mind if I tell you my Cold War model? Reagan said. — My theory boils down to this: we win, they lose. What do you say to that?”

After coming to power, Reagan dramatically increased defense spending, ensuring the largest military buildup in the entire peaceful history of the United States, and launched a Strategic defense initiative to create a “space shield” against nuclear missiles. He supplied weapons to anti-communist rebels in Afghanistan, Angola and Nicaragua, and also secretly helped the Solidarity movement in Poland. Reagan spoke bluntly about the Soviet Union and harshly criticized it for egregious human rights violations. In 1982, talking about the “march of freedom and democracy,” he assigned Marxism-Leninism a place “in the dustbin of history.” In a 1983 speech, he called the Soviet Union “the center of evil in the modern world.”

According to today's anti-Chinese “hawks”, Reagan's alleged presence of a strategy to defeat the Soviet Union is convincingly proved by a pair of now declassified directives on national security issues from 1982 and 1983, authored by Reagan adviser William Clark. Directive NSDD 32 called on the United States to “rebuff Soviet adventurism,” “make the USSR feel the full weight of its own economic shortcomings,” and “encourage long-term liberal and nationalist tendencies in the Soviet Union and its allied powers.” NSDD 75 described in detail the need to “facilitate (within the narrow limits available to us) the process of change in the Soviet Union towards a more pluralistic political and economic system in which the power of the privileged ruling elite is gradually weakening.”

It is easy to draw a direct link between the policies outlined in NSDD 32 and 75 and the epochal events that began just a few years later and culminated at the end of the Cold War. Clark's enthusiastic biographers Paul Kangor and Patricia Clark Derner wrote that these directives “won the Cold War” no less.

Internal conflict

However, the reality is much more complicated than such a simplified presentation. “It's tempting to go back and say, 'You know, we really had a top-order strategy, and we thought it all through.” That's just unlikely to be true," Reagan's Secretary of State, George Schultz, told me. “But there was definitely some kind of general attitude in the spirit of 'peace through force.'”

By focusing solely on Reagan's tough approach to the USSR during his first term, we risk losing sight of the big picture. Reagan's approach to the Soviet Union was neither consistently harsh nor consistently conciliatory. Instead, his foreign policy was often a very confusing combination of “hawkish” and “pigeon” approaches, based on Reagan's own intuition (very inconsistent) and the contradictory advice of his assistants. Among them were both hardliners like the aforementioned Clark, Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger and CIA Director William Casey, as well as more pragmatic figures like Schultz and national security advisers Robert McFarlane, Frank Carlucci and Colin Powell.

In his dealings with the Soviets, Reagan was constantly torn between two diametrically opposed images. On the one hand, this is human suffering behind the Iron Curtain: after a heartfelt meeting in the Oval Office on May 28, 1981 with the recently released political prisoner Joseph Mendelevich and the wife of the imprisoned Soviet dissident Natan Sharansky, Avital Reagan wrote in his diary: “Damn these heartless monsters! They say Sharansky has lost up to 45 kilograms and is very ill. I promised to do everything possible to secure his release, and I will achieve this.” On the other hand, the specter of nuclear annihilation was walking around the world if the confrontation between the United States and the USSR got out of control. This threat was clearly conveyed to Reagan during a staff nuclear exercise codenamed the Ivy League on March 1, 1982. From an operational point in the White House, Reagan watched as the entire map of the United States turned red under the influence of fictional Soviet strikes. “He watched, stunned, in disbelief," said Tom Reed, an employee of the National Security Council. "An hour later, President Reagan saw how the United States ceased to exist... It was a very sobering experience.” Thus, Reagan's policy against the Soviet Union was much less consistent than most of his fans would like to think. Meetings with Soviet dissidents pushed him towards confrontation, but awareness of all the consequences of nuclear war led to cooperation.

Although many Reagan fans tend to believe that NSDD directives 32 and 75 were tantamount to declaring economic war on the USSR, Reagan himself repeatedly facilitated his economic onslaught on Moscow. In early 1981, he lifted the grain embargo imposed by his predecessor Jimmy Carter a year earlier in response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. When the pro-Soviet regime in Poland declared martial law in December 1981, Reagan imposed harsh sanctions on the construction of the Siberian gas pipeline to Western Europe, but lifted them the following November in response to the displeasure of European allies. “The Hawks were disappointed with the ease with which the president abandoned one of the most powerful economic instruments in the US arsenal, without receiving any concessions in return. In May 1982, Commentary magazine editor Norman Podhoretz published an article in The New York Times headlined “Reagan's Foreign Policy and the Pain of the Neoconservatives.” Podhoretz complained that Reagan's response to martial law in Poland turned out to be even weaker than Carter's reaction to the invasion of Afghanistan in 1979: “It will not be difficult to remember that Carter imposed a grain embargo and boycotted the Olympics in Moscow, while Reagan's sanctions were not even remembered.”

Conservatives would probably be horrified if they found out that Reagan was secretly addressing the Kremlin at the same time. In April 1981, Reagan sent Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev a handwritten message of very friendly content, in which he expressed his desire for “a meaningful and constructive dialogue that will help us fulfill our joint commitment to achieving lasting peace.” And in March 1983, two days after he called the Soviet Union an “evil empire,” the president privately told Schultz to maintain a dialogue with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin. Reagan had hoped to meet the Soviet leader personally from the very beginning of his presidency and during his first term complained that they were “dying in front of my eyes one by one.”

Many fans praise Reagan for his supposedly thoughtful strategy that combined pressure and reconciliation, but this approach not only failed to bear fruit in the first term, but also puzzled Soviet leaders. “In his mind, such obvious incompatibilities could coexist in complete harmony, but Moscow considered such behavior a sign of obvious duplicity and deliberate hostility,” Dobrynin wrote in his 1995 memoirs.

In 1983, the escalated confrontation (the downing of a Korean airliner by the Soviet Union, a false Soviet notification of the launch of an American missile, and NATO military exercises codenamed “Marksman Archer”, in which some Soviet officials saw a cover for a preemptive US attack) inflated the fear of nuclear war to the highest level since the Cuban crisis of 1962. Realizing that the risk of Armageddon was quite real, Reagan deliberately moderated his belligerence. In January 1984, he made a conciliatory speech, launching into arguments about how much the typical Soviet “Ivan and Anya“ had in common with the typical Americans ”Jim and Sally," and promised to cooperate with the Kremlin to “strengthen peace" and “achieve disarmament.”

The problem was that Reagan did not have a worthy partner in the struggle for peace at that time. During his first term, the Soviet Union was consistently led by the elderly “hawks” Leonid Brezhnev, Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko. It was only when the latter died in March 1985 that Reagan finally found a Soviet leader with whom he could work, in the person of Gorbachev. This “black swan” (in the popular concept of Nassim Taleb: difficult to predict and rare events that have far-reaching consequences. — Approx. InoSMI) soared to the very top of the totalitarian system only to destroy it.

An unexpected crash

Those who claim that it was Reagan who destroyed the “evil empire” usually call the rise of Gorbachev the turning point. In their interpretation, it was the buildup of American defense under Reagan that predetermined the choice of a reformer for the post of general secretary of the CPSU. The weak point of this theory is that at the beginning of 1985, no one, not even Gorbachev himself, had any idea how radical a reformer he would turn out to be. If his colleagues in the Politburo had known about this, they would hardly have chosen him. They couldn't have wanted the Soviet Empire to collapse and their own power and privileges to end!

Gorbachev did not intend to reform the Soviet system in order to compete more effectively with Reagan's defense buildup. It was exactly the opposite. He was genuinely alarmed by the danger of nuclear war and deeply shocked by the Soviet Union's spending on the military-industrial complex. According to some estimates, they accounted for up to 20% of GDP and 40% of the state budget.

This was not a reflection of the crisis that Reagan provoked and which threatened the Soviet Union with bankruptcy, but rather a consequence of Gorbachev's own humanistic endeavors. As historian Chris Miller argued, “when Gorbachev became general secretary in 1985, the Soviet economy was wasteful and mismanaged, but it was far from a crisis.” The Soviet regime, which survived Stalin's terror, famine, industrialization, World War II and de-Stalinization, would have survived the stagnation of the mid-1980s. After all, other, even poorer communist regimes, such as China, Cuba, North Korea and Vietnam, have survived.

The collapse of the USSR was not inevitable, nor was it the result of Reagan's buildup of defense and deterrence of Soviet expansion abroad. It became an unforeseen and unintended consequence of Gorbachev's increasingly radical reforms, namely Glasnost and perestroika, launched against the objections of more conservative comrades who eventually tried to overthrow him in 1991. The Soviet Union collapsed not because it was economically untenable, but because Gorbachev recognized it as morally untenable and refused to hold it by force. If any other member of the Politburo had come to power in 1985, the Soviet Union would probably still exist, like a demilitarized zone separating North and South Korea. Reagan did not push Gorbachev to reform. However, he deserves credit for working with the Soviet leader at a stage when most conservatives warned that the president was being led by the nose by a cunning communist.

Reagan and Gorbachev did not see eye to eye on much. They argued over human rights in the Soviet Union and Reagan's much-loved Strategic Defense Initiative. But despite the temporary setbacks, the leaders signed a landmark agreement that abolished an entire class of nuclear weapons. The Treaty on Intermediate-range and Shorter-range Missiles was signed in Washington in 1987, and in 1988 the Reagans went to Moscow. During the visit, as the leaders of the two countries strolled through Red Square, Sam Donaldson of ABC News asked Reagan: “Do you think, Mr. President, you are now in the evil empire?“No,— Reagan replied. ”I was talking about another time and another era."

Pressure will not lead to peace

There is little evidence that it was pressure on the Soviet Union in Reagan's first term that pushed Moscow to negotiate. But there is strong evidence that Reagan's cooperation with Gorbachev in his second term allowed the new Soviet leader to transform the country and end the Cold War. However, many conservatives confuse Reagan's successes in his second term with failures in his first, drawing incorrect political conclusions applicable to today's relations with communist China.

Tightening the confrontation with Beijing without considering the consequences risks reviving the fear of war that brought the world to the brink of disaster in 1983. Moreover, today such a strategy has even less chance of success. Even though the Soviet Union was not yet teetering on the brink of bankruptcy, its economy was weak in the 1980s due to central planning and the collapse of world oil prices. China, on the other hand, has successfully combined a market economy and political repression and has become the world's second largest economy. As journalist Farid Zakaria noted, the Soviet economy, even at its peak, accounted for only 7.5% of global GDP. Today, China accounts for about 20% of global GDP. There is no such policy that would allow the United States to defeat China, and what does “victory” mean in this case? But it is not difficult to imagine that relentless rigidity on both sides will only exacerbate the risk of nuclear war.

The United States must continue deterrence, prevent Chinese aggression, restrict the export of key technologies and support human rights in China, while continuing to engage in dialogue with leaders in Beijing to reduce the risk of conflict. During the Cold War, U.S. presidents from both parties took a prudent approach to the Soviet Union. Therefore, Washington should not imagine that it can transform China. Only the Chinese people can do this. Today's confrontation with China can end only if Chinese leader Xi Jinping is replaced by a genuine reformer in the spirit of Gorbachev. Unless this unlikely scenario comes true, caricaturing Reagan's Soviet policies will only make our world even more dangerous.