What's wrong with the "Free World"

The Russian special operation in Ukraine has revived the Western concept of the "Free World", the consequences of which can go beyond rhetoric, writes Foreign Affairs. The author examines how the foreign policy of the "Free World" worked before.

Peter Slezkine

Why reviving the Cold War concept is a bad idea

The Russian special operation in Ukraine revived the concept of the "Free World". On the day of its beginning, the President of Ukraine, Vladimir Zelensky, appealed for support to the "leaders of the free world." In his address to the US Congress on March 1, US President Joe Biden stressed the "determination of the Free World." "The free world is united in its determination," British Prime Minister Boris Johnson echoed them three days later.

The return of the Free World is fraught with far-reaching consequences that go beyond rhetoric. From the late 1940s to the mid-1960s, America's quest for domination of the Free World led to a number of unintended political restrictions. Therefore, before becoming prisoners of this concept again, it would be wise to consider how the foreign policy of the Free World worked before.

A brief historical digression

On March 12, 1947, US President Harry Truman called on Congress to support a package of aid to Greece and Turkey in order to prevent the spread of Soviet influence in Southeastern Europe. Truman declared a moral watershed and demanded that Americans firmly take their side. In a situation where "almost all countries are obliged to choose from two mutually exclusive lifestyles," the US policy will be to "help free peoples defend free institutions and national integrity against aggressors who are trying to impose a totalitarian regime on them," he said.

The ubiquitous communist threat rallied congressmen in support of the bill. At the same time, the universal formulation of the future Truman doctrine assumed strong and worldwide obligations, which the White House was by no means going to fulfill. In the next few weeks after Truman's speech, supporters of the bill tried to establish a clear framework for American intervention, stressing that it does not follow from the aid of Greece and Turkey that other "free peoples" will be able to count on the same support. Republican Senator Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan, chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee and a key ally of the administration, made himself very clear: "I repeat emphatically: in this case we are not creating a universal precedent."

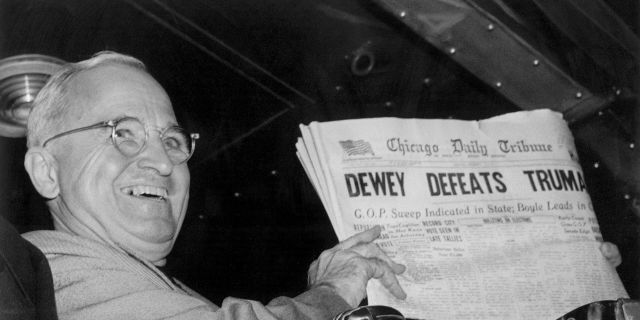

However, Truman's pathetic speeches about the confrontation between "free peoples" and "totalitarian regimes" brought down accusations on the administration that it was not coping with the global problem that it itself had designated. In November 1947, New York Governor and future Republican presidential candidate Thomas Dewey reproached the administration for inconsistency: it resists communism in Europe, and on the contrary, tolerates it in Asia. "The free world is now in the desperate situation of a man with gangrene of both legs – in Western Europe and in Asia," he warned. "And our government is telling the world that we have a wonderful cure for gangrene, but it is going to treat only one, and let the gangrene of the other leg kill the patient." The establishment of the communist regime in China in 1949 gave this argument political weight.

By the beginning of 1950, the Truman administration was already strictly adhering to the doctrine of two worlds. This point of view was reflected in the top-secret strategic document NSC-68, which essentially postulated a struggle on the principle of "who is who" between the "Free World" and the Soviet world. "Damage to free institutions anywhere" was equated with "universal defeat," and the United States was required to ensure "a rapid and decisive build-up of the political, economic and military power of the Free World." By its decision to enter the Korean War in the same year, the administration put the theory into practice, demonstrating the intention of the United States to protect the borders of the Free World everywhere. The doctor will not allow the death of the patient.

The adoption of the Mutual Security Act of 1951 consolidated the foreign policy of the Free World, combining the disparate efforts of the United States to provide military and economic assistance into a single program. Truman explained that the law is aimed at a three-way counteraction to the communist threat: "Firstly, the Soviet threat is global in nature. Secondly, the Soviet threat is total. Thirdly, the Soviet threat is indefinite." Although the US government has not stopped making distinctions within the Free World, any private support from now on required a holistic justification. So the Truman Doctrine with a claim to universalism became official policy.

Definition from the opposite

Perhaps the key feature of the Free World was its self-determination from the opposite. Government reports provided accurate data on free world trade and resources, and separately listed the communist countries that had been crossed out. As the Democratic Senator from Georgia Richard Russell (Richard Russell) remarked at a meeting of the Committee on Foreign Relations in 1951: "Everything that is behind the Iron Curtain, I call the Free World." William Fulbright, a Democrat from Arkansas, echoed him: "By "free" is meant "free from the rule of Moscow."

The confusion of the terms Free World and non-communist World led to difficulties every now and then. First, it forced the United States into a policy of global deterrence, despite the general fears that the country could overexert itself. Just a month after the outbreak of the Korean War, Massachusetts Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. asked Secretary of State Dean Acheson if such a general opposition to communist expansion is strategically durable: "Won't we sooner or later have to cede some areas captured by the Soviets? Otherwise, we will get involved in a hopeless confrontation around the world." Acheson agreed. However, in the next two decades, the United States continued to resist the onslaught of communism throughout the Free World, one and indivisible.

Another disadvantage of the doctrine of the Free World was that there was no possibility of non-alignment as such. According to the US government, all countries outside the communist bloc belonged to the free world by default. However, foreign states resisted the demand to take one side or the other – even under the threat of conflict with the United States. Thus, according to the Law on Mutual Security, any country receiving military assistance from the United States was obliged to contribute to the "defensive power of the Free World." In early 1952, the United States suspended military aid to Iran after Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh refused to make public commitments to the Free World. And when the Indonesian Foreign Minister signed a similar agreement in the same year, his cabinet collapsed as a result of a powerful internal protest against entering the "American orbit". In 1953, the United States and Indonesia reached an alternative agreement without military assistance, and CIA and British intelligence officers organized a successful coup against Mosaddegh.

Another unsolvable problem was the inability of the United States to offer a positive ideology to rally a Free world built from the opposite. The 1948 Congressional report emphasized the need to counter Soviet propaganda with a clear message: "One of the factors of moral weakness in the non–communist world and, conversely, moral strength in the communist world is the clarity of their ideas and our uncertainty." New injections into information programs already under the Eisenhower administration did not solve this fundamental problem. As one operative complained in 1955: "The weakness of the negative definition of the Free World and its philosophy lies in the fact that it does not offer anything concrete to the addressee." As a result, the Free World was a vast and heterogeneous collection of states, united by nothing but anti-communism.

The inability of the United States to strengthen the common faith in the non-communist world put politicians in a paradoxical position: instead of welcoming the obvious reduction of the Soviet threat, they, on the contrary, feared it. A 1951 report by the National Security Council expressed serious concern about the success of the Soviet "peace campaign": the Kremlin blamed the West for militarism and demanded a ban on nuclear weapons. "With such tricks, the USSR can lull the Free World into a deceptive sense of false security, which will negatively affect both its military strength and political cohesion." A 1956 report by the National Security Council issued a similar warning already with the beginning of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev's campaign for "peaceful coexistence." "If the USSR manages to improve its reputation in terms of peaceful intentions, this will lead to a gradual surrender of the positions of the Free World." The leadership of the United States in the Free World came from an enduring external threat.

New interpretation

In the 1960s, the Free World split along three different axes. Due to the routine of the Cold War and the Sino-Soviet split, the communist world has lost its unity and has become less threatening. The increased role of the less developed countries of the Free World has led to the recognition of a separate "Third World". And in the West, the growing countercultural movement has questioned how "free" countries really are. After the end of the Vietnam War, the "Free World" turnover practically disappeared from government documents. However, the legacy of this concept has been preserved thanks to the US craving for global leadership and the desire to support its military alliances.

Today, the term "Free World" is back in circulation. In its current interpretation, it seems to be synonymous with the West in general. At the same time, the conflict in Ukraine revealed a persistent contradiction between Western unity and Western universalism. Minus the formal allies of the United States (mainly Western), the attitude towards anti-Russian sanctions turned out to be at least ambivalent. For supporters of the Free World, such hesitation and a wait–and-see attitude are hardly acceptable - as recently demonstrated by the general pressure on India, Pakistan and other countries. The fact that the "West" is not suitable for synonyms of the "Free World" will become even more obvious after the acute phase of the European crisis has passed and the United States once again turns towards Asia. In its directive of 1951, after the previous reorientation from Europe to Asia, the State Department warned: "Keep in mind that there are free nations both in the West and in the East. Thus, the continuing caution regarding the East-West terminology remains."

Another prospect is that the "Free World" will serve only as a label for one of the parties in the struggle of democracies and autocracies, which the Biden administration likes to talk about. But the problem is that autocracy at this stage is a disease that has affected almost all countries in one way or another, including the United States itself. Such a "Free World" will become the complete opposite of itself. Attempts to isolate autocracy by outlining a certain group of "fit" democracies are fraught with certain difficulties. After his promise to re-give the "peoples of the free world" a single goal, Biden convened a summit for democracy, which came out crumpled and confused. Membership criteria turned out to be murky, and the future contours of the club were unpredictable. Moreover, if the reason for the existence of the alliance is some common values, not common security, then the basis for US leadership is no longer so obvious.

The simplest way to shape the Free World is to define its opposite. The new Free World will also seek self-determination from the opposite, excluding potential membership for conveniently contiguous Russia and China (as well as North Korea and the like). Washington's liberal internationalists have long given these regimes a textbook status in relation to other autocracies. The conflict in Ukraine has consolidated this status quo. Recent proposals to ease pressure on oil-producing states Venezuela and Iran in order to tighten pressure on Russia naturally follow from the foreign policy of the Free World. After all, the long-term struggle against absolute evil requires the mobilization of all available resources. As the Democratic Senator from Texas Tom Connally exclaimed in 1949, discussing membership in NATO: "I don't know how much democracy there is in Portugal, but it has the Azores."

It is possible that the revival of the Free World will be fleeting. Attempts to breathe new life into this concept during the so-called war on terrorism have not been successful. But rhetorical categories have their own inertia. A new belief in a Free world from the opposite will give rise to the usual set of problems: an insistence on seeing decisive trials in distant wars, intolerance of non-alignment, inability to formulate a common goal in positive terms and reliance on an enduring evil in the form of an external enemy. It is not too late to develop a flexible and regionally oriented foreign policy that does not require worldwide mobilization against a single existential threat of a global nature. Trying to lead the supposedly Free World is by no means a winning strategy. On the contrary, it is a trap.